The State of the Irish Fisheries in 1836

The quay of Clifden is near the eastern extremity of Ardbear Bay, contiguous to the village, and on the estate of Mr. John D'Arcy. Clifden is not a place of rendezvous from whence boats proceed to the fishing grounds, being too far embayed; but its utility consists in affording a safe landing-place, and a certain market for fish to any amount, and in supplying all necessaries for the outfit of the fishery and merchandise for the country in general; there being extensive stores erected on the quay for the curing of fish. And the supply of the necessaries mentioned above. The village is entirely a new creation, and owes its rise to the establishment of the Harbour, and opening the country by the Government roads that have been made.

The plan which was given by Mr. Nimmo consists of a Boat and slip quay, five hundred and eighty nine feet in length, with an elbow or obtuse turn along a cliff three hundred feet in length, for shipping of deep craft, but only one hundred and seventy five feet of the ship quay is finished, and three hundred and fourteen feet in length of the boat quay has been raised within two feet of its intended height. Sixty seven feet of the ship quay, the entire three hundred feet of the elbow or deep ship quay and two feet in height of the boat quay remain undone. Under the contract this work should have been completed on or before the 1st day of August 1823.

In 1822 the Board granted £228 9s 2d towards the expense of this work, including the cost of erecting a breakwater at Doughbeg, about a mile westward of Clifden; the amount of the estimate of the whole being £456 18s 5d; in addition to which, the Board supplied machinery to the value of £34 19s, and contracted Mr. D'Arcy, who undertook to contribute £288 9s 3d for the executions.

The Board agreed to pay Mr. D'Arcy in instalments, as certain portions of the work would be certified by the Boards engineer to have been duly executed; under which clause Mr. D'Arcy received payments amounting to £168 16s, including the value of machinery, and £94 12s 2d now stands to the credit of the work.

It may be proper to observe, that £342 9s 1 and a ½ d (Irish) is charged to Government as expended on this work, exclusive of the foregoing sums.

It is obvious that the work was inadequate to the expense of executing such extensive works, and believing it was not probable they would be completed without the Board's interference, in November last I recommended that the balance standing to the credit should be expended in completing, so far as adequate, which would secure and finish as much of this interesting Harbour as would be at all necessary for fishery objects, and I now respectfully repeat that recommendation.

This Harbour may be placed in the second class for its utility in promoting the fishery.

The breakwater at Doughbeg was included in the foregoing estimate, though a distinct and detached work. It was finished, and is a useful work; it stands in need of some trifling repairs, but the damage being the effect of mere wear and tear, I do not conceive there is any fund applicable to it.

Extract from Mr. Donnell's report of 1829- Notwithstanding the unfinished state of the greater part of these quays, some good stores have been erected on the finished part, and merchant vessels load or discharge their cargoes at them. They bring iron, pitch, ropes, earthenware and take away fish, corn, kelp and Irish Marble.

A few years back there were only some poor scattered cabins about this place; at present there are, exclusive of merchant's stores, several streets of slated houses, church, chapel, School, bridewell, distillery and police office.

The place was heretofore only remarkable for illicit distillation and smuggling; at present it pays excise duties to a considerable amount.

Eight mooring posts and three mooring rings have been fixed in the quays, under the general order for moorings.

Appendix- Conditions of the Fishermen.

Conditions of the fishermen

There is no difference in the morals and social circumstances of the fishermen and agricultural labourers on this coast (Killeries); both pursuits are combined in the same person. For every man who has land is a fisherman, which causes him in a great measure to neglect both; the double pursuits injure both avocations, and if they could be separated by building fishery villages for the fishermen, I think the fisheries would improve, and the conditions of all parties much bettered; and it is my opinion that fishermen may be employed on this coast advantageously every day in the year, fishing or repairing fishing materials.

There is no difference between the houses of fishermen with land and those without it, in both cases they are generally very uncomfortable, or rather they are miserable. Most of the land in this county is in an uncultivated state, except patches along the shore, and generally let very low. When land is let for reclaiming, the rent is about 5s an acre. Favourably situated cultivated land lets at from 12s to 25s an acre; and the little let as con-acre, brings, with sea-weed, from £3-£4 per acre.

In some seasons, fishermen earn a good deal by fishing, but in other seasons, not being provided by capital, when the Herring season commences, they are compelled to purchase on credit, and often before they are ready to attend the fishing, it is over. This causes great distress: but it is the consequences of their not being regular fishermen, and always prepared when the fishing commences. – (Colonel Thompson.)

The fishermen of Scotland have small kilns attached to their houses, for drying fish, Most of the fishermen on this coast are farmers, and a few are agricultural labourers. The use of ardent spirits does not prevail to an injurious extent. The fishermen not being wholly employed in fishing, in consequence of other pursuits, is most injurious to the fisheries – (Mr. D'Arcy.)

The Islands on this coast (Connemara) suffered in common, from famine in 1819, 1822, and 1830. The cause was, in my opinion, the change in the value of money. The price of pork having fallen below a remunerating price, the people ceased to raise a surplus of potatoes for the food of the pig, and therefore had nothing to fall back on in a scarce season.

I am of opinion, that every famine which has taken place in Ireland, can be proved to have followed some unnatural check on national or individual industry; and that the contraction of the circulation in England, and the consequent fluctuation of the markets, will always be followed, at an interval of about two years, by a famine in the west of Ireland.

The fishermen are not wholly employed in fishing; they are chiefly engaged in agriculture; but people of all classes join more or less in the Herring fishery. A division of labour would be injurious to the fishermen, while our population is so much scattered, and the means of obtaining the necessaries of life so easy.

An industrious fisherman, paying in rent only one-fifth of the gross produce of his land, and fishing in his leisure hours, (for there is no occasion to work more than four months on the farms) may get quite wealthy even on three or four acres of land. A mere fisherman could hardly exist. Con-acre rent is about double that of farms.

The widows of fishermen generally occupy the lands held by their husbands, and I have always found them the best tenants. I consider absolute destitution very rare indeed. – (Mr. Blake.)

The Islands of this coast are sufficient to maintain the inhabitants, unless in seasons of famine, occasioned by storms, or some other cause. All the Islands on the coast have been remarkable for being more severely visited with famine than the mainland, as they are more exposed to the westerly wind, which generally prevails on this coast; and when it blows with violence, unaccompanied with rain, in the month of August, it is sure to destroy the potato crop, by burning the stalks. This wind is called, in the country, the red wind. When famine presses heavily, the Islands and mainland receive relief from charitable societies in England, and the Government.

There is very little con-acre in this district (Clifden), and when it is let, a share of the crop is retained by the owner of the soil. When land is let manured, a larger share of the crop is demanded. If this plan was generally adopted through the kingdom, fields of potatoes would not be left in the ground to rot, sooner than pay an exorbitant rent; and it would prevent the law proceedings for the recovery of con-acre rent.

In the winter of 1825, each row-boat, on an average, cleared £10; at that time, at least 2,000 row-boats were fishing. The take of fish has since fluctuated very much, until last season, which was rather good, some row-boats having taken from £30-£45 worth of Herrings, although Herrings sold cheap. – (Mr MacDonnell.)

The Islands of Aran, about thirty miles in circumference, are the property of the Digby family; Population, about 3,000; diminished, within the last three years, 500, by emigration to the United States of America. The Aran emigrants are employed in fishing between Boston and New York, where they obtain a comfortable livelihood; and many others would have gone there this year, but were disappointed in a vessel to take them out; in fact, the passage money had been paid to a person in Boston, by their friends and relations. Now, in my opinion, were employment afforded at home, by the establishment of a company, they need not to have gone abroad. The rental exceeds £2,000 per year, which is considered high, and several tenants are in arrears; the rent of each is from £2 to £6. Some have short leases, and others are tenants at will. They maintain themselves partly by fishing, and partly by agriculture. Distress has been felt in Aran occasionally, as well as in Connemara, by blight of potato crop, particularly in 1822; and relief has been afforded by the proprietor, government and private subscriptions. – (Mr. Morris.)

The fishermen in this district (Clifden) are engaged in agricultural pursuits, which I think injurious to the Fisheries and to agriculture. If they could be separated, it would be desirable, and beneficial to both pursuits; but I think it will take a long time to accomplish it. If the fishermen were congregated into villages, and separated from farming pursuits, and the farmer to employ himself in tillage instead of fishing, it would benefit both parties. - (Captain Andrews.)

All the male inhabitants of Cleggan are more or less fishermen. They are destitute of every convenience; they live in the most wretched hovels that can be described; they are yearly tenants, generally holding lands under freeholders, who themselves are miserably poor. I know of no con-acres let here. The condition of the fishermen is so wretched, that any change must benefit them. The aged are supported by their neighbours, and the widows by begging. –(Lieut. Warren, R.N., C.G.O.)

The most of the fishermen of Mannin bay have small farms for potatoes, corn, and the grass for a cow. I do not know if it has any effect on the fisheries. Those who have land are best off; without it, they would be hard set to support themselves. When not employed in fishing, they go as agricultural labourers, at 6d. or 8d. a day.

Stubble land, without manure, is let for £2 an acre; the average rent of farms is about £1 10s per acre. If the fishermen were congregated in towns, and schools established for education, and instruction in modes of net making, their conditions would improve. – (Mr. Burtchael, C.G.O.)

A loan fund has been lately established at Clifden, but on so small a scale, as to be of little use.

I do not perceive any good effect from the loan fund of the late fishery board; but the fisheries failed at this period, and there was also a failure of the crops along the west coast. At the time of the late fishery loan, fishermen were charged usuriously, as they could not obtain bail or security, unless through the persons who had fishery materials for sale; and for giving security, these persons charged their own price. – (Mr. D'Arcy.)

The assistance from the late Fisheries board rather injured than benefited the borrowers in this district (Renvyle), as it was followed by bad seasons, and the demand for repayment came upon them when greatly distressed. Its failure could not be ascribed to the imprudence of the borrowers. The condition of the people can never be permanently improved by temporary assistance or legislative interference. Steady markets alone stimulate industry and afford employment.

I am of opinion the Agricultural and Commercial bank will do all that is necessary in future as to loans; and the assistance of governments should be confined to piers, harbours, and roads, including bye-paths to creeks. – (Mr. Blake.)

No doubt the loan fund of the late Fisheries Board rendered service, but not that of permanent nature as would be desired. In many instances, it was used in discharging debts to shopkeepers, buying clothes, and other things, and not by any means for the Fisheries or their improvement. – (Mr. MacDonnell.)

I know of no loan fund or savings bank on this coast (Cleggan); the fishermen are too poor to have money in a savings bank.

I do not know the effect the loans of the late Fishery Board produced, but I think a loan to fishermen on this part of the coast would be entirely lost. At present, the fishermen cannot obtain credit on any terms. – (Lieut. Warren.)

I do not consider, on the whole, that the loan fund has been productive of any good effect. I know it gave rise to a system of raising the wind, in order to pay rents to landlords, in which cases the loans were recovered at an expense greater than the amount lent-for inspectors, travelling charges,- and a great number has not been recovered at all. Moreover, when an order was given to a shopkeeper, who notoriously had an understanding with the inspector, it was partly paid in cash, partly in goods of an inferior description, and at an enormous price, and very often not a shillings worth for boats or nets. – (Mr. Morris.)

The end of the 18th century and the early 19th century was the boom time for Irish gardens. Before this the situation within the country was not conducive to the construction of gardens. Obviously there would have been some gardens and most houses would have had vegetable gardens, but the idea of pleasure gardens was novel.

As the large estates began to be developed the formal park and walled garden came into vogue, you can find these estates all over the country, a good many are open to the public. Connemara on the other hand had no such large estates. Certainly the Martin estate was large, in fact one of the largest in these islands, but they were chronically short of money and probably enjoyed the rugged outdoors rather than any formality.

Trees and shrubs as well as herbaceous plants began to sweep the country, this plant material arrived from the four corners of the globe. The British empire was beginning to expand and many Irish were amongst those working or soldiering in foreign lands. On top of that the professional plant hunters were sending vast amounts of plant species back to the homelands. Naturally some of these trees and plants, moved west and the various landlords would have tried to outdo each other with their exotic plants. There are some fine old specimen trees in different estates in the area outside of Galway, and even a few in Connemara.

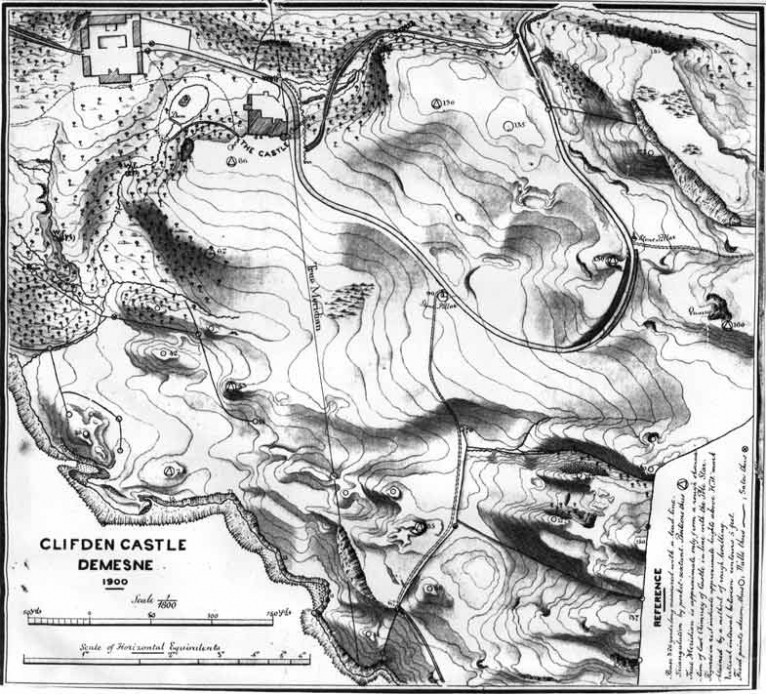

I like to think that John D’Arcy of Clifden Castle would have been one of the first landowners to have created a garden, in this area. When he built his castle in the early years of the 1800’s he planted trees to act as both shelter belts protecting him from the westerly gales, and to beautify his park. He would have been familiar with good horticultural practices from his estate in Kiltullagh in east Galway, which was surrounded by other model estates.

According to Hely Dutton in his “A Statistical and Agricultural Survey of the County of Galway” of 1824, Mr D’Arcy is an improving landlord who carries out all the best practices in land management. Hely Dutton should know about these things as he is described as a landscape gardener and land improver.

He mentions John D’Arcy frequently as in this section on the cultivation of green crops. “I may have omitted the names of others who know the value of green food, but I trust the good sense of the gentlemen of the county will before long, prompt them to pursue this very profitable branch of rural economy.”

Later he praises him on horse breeding. “Mr D’Arcy of Clifden has acted more judiciously; he procured a very beautiful small sire, who I am informed has left a very improved breed in Cumamara (sic). It is thought that the general breed of horses in this county is far from improving.”

He is also full of praise for Thomas Martin, well almost full. “The country about Ballynahinch the seat of Thomas Barnwell Martin Esq. is extremely bold and highly picturesque, totally different from any thing to be met with in any other part of this county. I am grieved to say, that nature has all the merit; she has had little assistance, though an almost constant residence for upwards of fifty years would lead one to expect that a small part at least of a large income would have been annually expended in improvements. Mr Thomas Martin, who is a young man, and has only lately got possession of Ballynahinch, is, as I am informed making preparations to plant extensively …….. But from Mr Thomas Martin’s love for planting, and every improvement, we may hope Ballynahinch may become what it should have been.”

Getting back to Clifden Castle, we find a reference to the gardening skills of John D’Arcy in Samuel Lewis’s A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland from 1837. “At a short distance, on the northern side of the town, is Clifden Castle, the delightful residence of John D'Arcy, Esq., the proprietor of the district, by whom it was erected. It is a castellated house standing on the verge of a fine lawn sloping down to the bay, and sheltered behind by woods and a range of mountain; the view to the right embraces a wide expanse of ocean. The pleasure grounds comprise about fifteen acres, and are adorned with a grotto of considerable extent, through which passes a stream, and with a shell-house or marine temple, composed of shells, spar, ore, &c.; though on the shore of the Atlantic, the trees and shrubs flourish luxuriantly.”

This description gives us a picture of a typical 18th century parkland setting, John was obviously influenced by the style of gardening in vogue at the time of his birth. It is fascinating to see that some of the structures mentioned in the above description are still standing. Sad to say very few of the trees mentioned are still in existence, but a number are of great age. As we can see from the map of the castle, albeit from a much later time, these features are still visible.

One plant Valerinia Pyranica, or Pyrenean Valerian, which still grows in the area and in my garden in particular, dates from that time. According to the book, Plants of Connemara and the Burren, by David Allardice Webb and Mary JP Scannell, the first mention of this plant is growing at Clifden Castle in 1835.

A number of other gardens in the area date from the early years of the 1800’s. Cashel House Hotel, has one of the oldest and most distinguished gardens in the area. Some of the exotic trees growing here are reputed to have been planted in the late 1700’s. The present house and garden date from the middle years of the 19th century. It has always been fortunate that the various owners have been passionate about gardens, and the collection of trees and shrubs have grown since those early years.

The D’Arcy houses, Glenowen, now the Abbeyglen Castle Hotel has a number of fine trees from the early years, Malmore is a well wooded estate and Glen Ierene, now Gleann Aoibheann, has many original trees and plants. A quick tour of Connemara, will show you the places where these old estates were built, as they are the few places where you will find trees. Errislannan Manor would be contemporary to these other gardens.

Of course the great era for gardening in Connemara, was the late 19th century, with the most important garden ever constructed in the area, this is of course Kylemore Castle, now Kylemore Abbey. This large and interesting garden was built by Mitchell Henry in the late 1860’s, At some other time I will give more time to this marvellous garden which is being restored.

Breandan O Scanaill.

The Galway to Clifden Railway Featured

The Galway to Clifden railway was in operation for forty years from 1895 to 1935, it was a single line of standard gauge, 5 feet 3 inches, with a total length of 48 miles 550 feet. The line ran through central Connemara and had seven stations, Moycullen, Ross, Oughterard, Maam Cross, Recess, Ballynahinch and Clifden. It took five years to construct and cost over £9,000 per mile.

Work started on the line in the winter of 1890, during a time of severe hardship in Connemara. A period of distress prevailed throughout the region due to bad weather, crop failure and falling agriculture prices. The people were in need of urgent assistance and the government considered the construction of a railway line was the ideal way of offered large-scale employment over a wide area. Up until this, railways were built by private enterprise and several attempts to construct a railway linking Galway with Clifden had failed due to lack of funds. However, by 1888, the government had decided that, in order to advance the rail network throughout the country it would offer grants for the construction of railways in remote, thinly populated districts that were considered commercially non-viable by the railway companies.

The Galway to Clifden line was constructed by the Midland Great Western Railway Company at a cost of £410,000, with an additional £40,000 going towards rolling stock. A large portion of the cost, £264,000, was granted as a free gift by government, under the Light Railway Act (1889). The company was to build, maintain and operate the line.

There were two engineers and three contractors involved in the construction of the line. The engineers, John Henry Ryan and Professor Edward Townsend, were both graduates of Trinity College Dublin and Townsend was Professor of Civil Engineering at Queen’s College Galway. The contractors were Robert Worthington, Charles Braddock and Travers H. Falkiner.

In order to bring employment quickly to the people, a provisional contract was entered into with Robert Worthington and preparatory works were started in autumn 1890. By January 1891 there were 500 men working along the line, at an average wage of twelve shillings a week. Over 200 of these took up lodgings in Clifden to avail of the work, while others were accommodated in wooden huts along the route. Each hut contained ten beds and a stove, and in some huts there were two men to a bed.

As the work progressed, the engineers became unhappy with the standard of Worthington’s work and he failed in his bid to win the final contract. The contract instead went to Charles Braddock. In April 1891, Braddock had notices in place along the line offering employment to all who would apply; by May he was employing almost a thousand men and boys. However, a year later, Braddock was running up serious debts throughout the county and failing to pay his workforce. There was a strike along the line that was only resolved with the promise of more regular wages. This, however, proved false and when Braddock was eventually declared bankrupt the MGWR Company was forced to take back the works in July 1892.

The contract was then passed to Travers H. Falkiner, who went on to complete the major part of the work. Under Falkiner, at the height of construction, over one thousand men were given regular employment along the line and the number rose to one thousand five hundred on occasion. Skilled men were brought in from the outside but the local workforce carried out the majority of the labouring work. Supply huts were erected in Ballinafad to serve the need of the workforce and shebeen houses were opened along the line. Falkiner, with the support of the local priest, tried to have the shebeens closed down, but failed.

By far the most interesting feature on the line was the viaduct across the Corrib River, the stacks of which can still be seen today. This was made up of three spans, each of 150 feet, with a lifting span of 21 feet, to allow for navigation of the river. There was just one tunnel on the line; this was a ‘cut and cover’ that carried Prospect Hill roadway over the railway. In all there were twenty-eight bridges, thirteen small accommodation bridges (bridges under 12 feet span) and numerous culverts to facilitate the sudden increase of water following heavy rainfall.

The seven stations all had passing places or loops, with up and down platforms, except at Ross and Clifden. Those stations situated close to Galway were faced with limestone taken from local quarries, while others further west were of red brick and roofed with red tiles. There were 18 gatekeeper cottages, situated at level crossings on public road.

The line from Galway to Oughterard was opened on 1 January 1895 and the rest of the line came into operation in July. As had been hoped, the opening of the line assisted the development of agriculture and fisheries in the region and contributed greatly to the economic stability of the area, particularly through its role in helping to establish Connemara as a tourist destination. The route was never profitable and in a bid to improve traffic on the line, the company embarked on a determined marketing campaign, advertising widely and offering packages that included tickets from many destinations in England with accommodation at their hotels at Recess and Clifden. For the home market, during the years 1903 to 1906, there were special tourist trains laid on during the summer months, offering day trips from the east coast to the west.

The world war and local wars brought a decline in tourism in the early decades of the 20th century. In 1924 a merger of railway companies brought the Galway to Clifden Railway into the hands of the Great Southern Railway Company and the line was reported to be in need of a good deal of repair. Traffic had dropped due to competition from private haulage companies and an increase in private car ownership. Despite local protests, the Great Southern Railway Company took the decision to close the line and the last train left Clifden on 27 April 1935.

Image Gallery

What makes a saga, formal history? How does lore become fact? When bits and pieces -- recollections, traditions, memories -- find themselves laid down on the page, or passed down in oral yarns or song. Those are the chronicles that ensure longevity, a place in collective consciousness, a position within a canon.

Some stories elude the official narrative - by chance or by design. For Paddy Moloney, someone both steeped in and inextricable from Irish culture - its turbulent history, its voluble folklore, it's very atmosphere - what vexed him was the fact that he grew up not knowing much at all about an unusual band of Irish soldiers known colloquially simply as the San Patrcios, a story that would seem a linchpin chapter in not just Irish but U.S. and Mexican history. How could a story about a band of daring Irish expatraites, who fought against America alongside the Mexican Army in the mid-1800s, slip so far into memory's margins, live so far outside of history?

Conveying Ireland's history and hardships through its legends, lullabies and laments, Moloney has been tending this very territory, both as a solo artist and the founder/leader of the Irish consort, The Chieftains, for nearly five decades. This "forgotten" piece of Irish lore seemed an essential story to tell, one begging for its proper framing, yet remained difficult to wrestle down nonetheless. If anyone should tell it, it would seem Moloney's province.

Puzzling out a way to fill in the picture and set this piece of jagged people's history into its proper context haunted him on and off for a good part of 30 years. "The whole thing of this," Moloney explains "It's kept coming back to me." San Patricio, the new album from The Chieftains, part excavation part celebration, is a souvenir of a long, circuitous journey across centuries, continents and the powers of imagination.

It's a story so vivid and sprawling, as Moloney saw it, that ultimately it would take several narrators, points-of-view, styles to give it its proper heft and feel, a panoramic document that felt as if it reflected the fusion of two cultures and the sui generis hybrids that sprung from it.

Recorded in Dublin, New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Mexico City and co-produced with longtime friend and sometime collaborator, Ry Cooder, the album is a collage of set-pieces each detailing a glinting shard of the story. The nineteen tracks feature a roster of artists who cross and thus blend genres -- among them: Linda Ronstadt, Los Tigres del Norte, Los Folkloristas, Moya Brennan, Lila Downs, Van Dyke Parks, Los Camperos de Valles. Liam Neeson also lends his voice, retelling the bloody climatic battle scene and Chavela Vargas, the 92-year old Mexican ranchero singer reports from some remote region of the heart. "I tried to cover all the moods and modes and instrumentation and different styles up and down the country," says Moloney, "Punctuating here and there. Just reminding you that this is what it's about."

For Moloney, the question wasn't so much the angle but the portal: Where to enter? The story of the San Patricios was a topic, even in later years, polite gentry tended to circle around, one seldom pursued too deeply: "I was fascinated by the fact that they were -- their existence -- kept so quiet," says Moloney. "You didn't speak of them. Especially among the Catholics. Especially here in Ireland."

Some years back, he recalls, a musicologist friend had been trying to entice him about a project dealing with the American Civil War, "'Wouldn't that be a perfect subject for you?' he'd said." But in the midst of his pitch Moloney got stuck back in another piece of the story, .". . , this ‘great Irish battalion.' And of course I was fascinated because it wasn't the hip thing to be speaking about because - as so many began to understand it -- they were deserters who were hanged for ‘going over' to the Mexican side."

The San Patricios, known also as The Legion of Saint Patrick, were men who had fled the Ireland's Potato Famine of1845 to try to start a new life in America only to find themselves ensnared fighting another country's war. Some enlisted, lured by the promise of advance pay, property, others were conscripted, but it didn't take long for them to understand that this war's goals felt familiar and were dubious at best and the new soldiers were suffering under conditions - religious bigotry, substandard living conditions, etc. -- that they had hoped to flee. Many of them, says Moloney, "were kind of turfed into the American army without a choice in the first place. They got off the boat at Ellis Island and then, ‘Here's a gun and go down there and shoot the Mexicans.' That didn't go down well with Catholics as they were, shootin' Catholics."

Many of these soldiers became part of the thousands of infantrymen who deserted, many of whom swam across the Rio Grande, unwilling to fight what came to be known as "Mr. Polk's War." It was one of the first battles that inspired vociferous opposition among Americans, according to Joseph Wheelan in his comprehensive 2007 study of the conflict, Invading Mexico, "[The war] was not so much due to [a] dispute over Texas's putative border as to [President James Polk's] eagerness to divest Mexico of California and the New Mexico territory and thereby fulfilling her ‘Manifest Destitny,' ". ". . . . But [the President] did not foresee that expansionism would kindle a bitter debate over slavery, resulting in the catastrophic American Civil War."

While American newspapers were reporting the country's unity the story on the ground was something all together different, historian and political scientist Howard Zinn argues. The U.S. Army struggled to not just assemble but maintain an army. Young men were enticed with promises of land and money, but their numbers dwindled after word circulated about the abject conditions and unchecked violence committed. It set off a surge of desertion that was difficult to stem.

Once on the other side, many of these Irishmen took up rifles and fought against the very American soldiers who had tricked and abused them, to defend Mexico from the American incursion. Led by John Riley, also a deserter, the battalion marched under a green banner. "He was from Conamara) and was a native Irish speaker," says Moloney. "He came from that part of the world where you only spoke Irish. But he formed the battalion and they fought to the bitter end.". " Ultimately, at war's close many were reprimanded, court-marshaled, hung, and some even branded, literally, as deserters (a "D" burned into their cheek) and left to wander.

Their story was eclipsed largely by the devastation of the American Civil War, which followed close afterwards, the high desertion rate of enlisted men which often rendered the topic of the war taboo. Mexico, which was left to attempt to recover from its losses and disarray -- left those who were keeping score (and official record) to deem the San Patricios' actions nothing less than treachery - both by the both the Americans and the Irish back home.

When you're left with mostly silence, holes and ghosts where do you start? For Moloney, it was then, a matter of conjuring spirits, "And I have a wild imagination. " As a touchstone and model he thought back to earlier projects that required a form of psychological teleporting, "Like "Bonaparte's Retreat," which explores the Irish connection to French history. That was thirteen minutes long. It too was a tone poem. So something like this? - This is like spreading your wings."

It began as a process of immersion, walking back into it, the sources. "I go with my good feelings and thoughts. People say, ‘You must have read about this, or heard about this there. ‘Actually, I go to the place and meet the people and you get the feeling -- and that will lead to something else. "

Winding back into those locations, along the trail of the diaspora - Cuba, South America, Mexico-and into the very lines of those old songs, Moloney began to hear similarities, fragments of melodies that were eerily familiar: Marks of Europe that were left in Mexico, the Irish influence left like a coat on a hook in a dark corner of a closest, evidence of what transpired linking past to present.

He followed the trail of the music and in the process, "discovered the similarities" There it was "in the mazurkas, jigs, polkas, and that of course is dealing with our [Irish] music as well." And some of the melodies so like ours," he explains. "One song, in particular, "Persecucion de Villa," that melody is so like one of our own Irish rebel tunes called, "Kevin Barry," who was also a patriot. There were a lot of Irishmen in South America, Cuba, and this happened in Mexico as well. "

With each trip, each conversation he'd have a bit more, another paragraph, another detail, and he'd fit it some safe place in his mind. "I was always getting great encouragement when I was back here at home from all sorts of people - like from the Mexican Ambassador, who even passed on some tapes and stories."

He'd regale some with his latest finds. One particularly keen and receptive listener was Cooder, whom he'd been sharing enticing anecdotes with for some time. "He always understood it. The music. It's power."

After one of those storytelling sessions about a dozen years ago, Moloney recalls, "Ry got after me and said: ‘Look, if you don't do this, I will. Maybe not quite those words, but I got the message . . . "

Cooder remembers it squarely the same: "That's right. And I meant it. I didn't want him to put it away - because Paddy is always moving. Always doing something else. Paddy needed to be doing this."

For Cooder, the peculiar resonances didn't crop up just in the music, but most significantly in history's reprise. "I told Paddy, there is timeliness to this. Do this now. Here we are now involved in this war that has similar overtones, this shockingly preemptive thing," says Cooder, "I'd studied up on what happened, and reading about it is like reading about the last ten years - all the events that drew us into this: A preemptive war, a broken faith election. The timing is amazing. It's a coincidence that might work in his favor if it could be handled in just the right way."

He was very helpful because he was so aware of it," says Moloney. "He delves into anything like this that's controversial - things that need to be brought out, understood."

About six or so months ago, says Moloney, the project got some real traction. Musicians brought things along as one would to a celebration -- instruments, ideas, forgotten stories behind melodies.

As well as musicians, ideas and approaches, Cooder carried with him some pieces to add to the mix ("Sands of Mexico" and "Cancion Mixteca" ). "He also brought the mariachis, that big raucous sound," says Moloney. "He brought who he knows -- and he knows them all. All the great players. He knows what's on the ground. He lives it.."

Ronstadt brought with her a family antique, "She came to the party with a lovely, beautiful song ("A la Orilla de un Palmar" )that she got from her grandfather, who is Mexican, that has to do with an orphan girl and that would have happened after the Civil War and you being to see, how it all sort of fits."

Often though, inspiration came serendipitously and Moloney tried to create space - time to talk, to explore to be open to it. "When we went to Mexico . . . people came out of the woodwork to play. One woman, Graciana Silva, I'd learned, played way up in the mountains. She often came down in the square in her little town and would have a coffee and play there. And there is where we found her. "

There was chance, yes, but there was also some up-front planning, Moloney explains. And without the early assistance of Guadalupe Jolicoeur, an Argentinean radio programmer who'd spent years researching the music of South America and Mexico, Moloney says he might still be puzzling this all out. She introduced him to a river of source music that served as a foundation and jumping-off point - it helped to train his ear for what to listen for: " It was a "Who's Who and What's What, really," says Moloney. "She was a whole book of history for me. So I had loads to pick from." From this playlist of material he'd create, "what I felt: was a typical Chieftains mix - a sort of fusion. For instance a lot of the music I actually composed, I used little bits . . . of old Irish melodies to mix in with the Mexican melodies. You'll hear that particularly in the Lila Downs tracks ("La Iguana" and "El Relampago" ) and Graciana's track ("El Pajaro Cu"). [Graciana] couldn't believe that this could happen. It was like a Mexican tune for her, one that she hadn't heard before."

Each artist, each song, wasn't just telling a piece of the story, but lending a different perspective or mood. What was it to march to your death for something you believe in? What was it to make of a life with your parents, grandparents - your ancestors -- gone? What was it to dream a future in a place so far from anything that was comforting or familiar? What was it to stand on the gallows?

In sessions, particularly like those with Los Tigres del Norte, the grand norteño ensemble from Rosa Morada, Sinaloa, the challenge, says Cooder, was creating an atmosphere that both suited the material and conveyed a very particular authenticity - a sense of verisimilitude of a moment, of a time.. "We needed a feeling of being in a dance hall. It's an environment. This is not a studio record but an experience record." So the challenge became to in some way transport the ensemble to that place in their own minds. "They came up in dance halls, so they now what that's like. We had the ambiance in the studio, fairly high ceilings," says Cooder. "Through the course of the day, I put the bass player on upright [figuring], the closer you go back to the origins , the closer to you'll be to the time of the origins of the song,, and the closer you will be, yourself, to the song."

History holds messages: lessons, cautionary tales, if we choose to listen. "War," says Cooder, "in every case, robs the people who make it out of the chance to be good."

By digging out and dusting off the story of the San Patricios, Moloney is reminded of how important it is to stand for something, how the notion of "good" or "truth" can never be entirely submerged - though it so often takes a beating.

Like nothing else, in its best incarnations music is history, archeology, commemoration all rolled into one. It eludes time. It's spirit wrapped in song:

Moloney has seen it with his own eyes, "This project has given me another boost," he says, "My wife used to keep telling people, ‘He's ten years rehearsing for retirement' But, no, it's coming back to me so strong now. This has done it."

For so long, this story had "so much shame wrapped around it. It wasn't in the history books," he explains. And while the San Patricios were long considered heroes in Mexico - with even a commemorative display in a Mexico City museum that enumerated the names of the soldieries lost - it wasn't until 1997, 150 years later, did both the Irish and Mexican government hold a joint ceremony to celebrate the contributions of the San Patricio Battalions. "It took that long."

What Moloney hopes, is that people who listen will see what he saw, feel what he felt. "I'm hoping they get the vision of what I've conjured in my mind through music in telling this story. It wasn't all doom and gloom. There were some happy times. You'll hear that on the record. The same as it was with the Irish on their own land. In many ways it's a very typical kind of Irish story - you know, about the terrible time we had with the neighbors who came to visit and forgot to go back.," he says. "There's a lot of similarities between what happened here as well. It's not a massive beef but it is a very important story. A very important light has lit up in a historical event that took place. And without getting really crude and hard about who was right and who was wrong: it's all history now. But it's something that should be told. A story that's been waiting."

Article reproduced by kind permission of The Concord Music Group: http://www.concordmusicgroup.com/artists/The-Chieftains-featuring-Ry-Cooder/

Batallón de San Patricio: the Irish Heroes of Mexico

Paper appears courtesy of Martín Paredes - http://www.martinparedes.com/

Introduction

On September 12, 1997, Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo held a ceremony in Mexico City in honor of the 150th anniversary of the San Patricio Battalion. Representing Ireland, Ambassador Sean O’Huighinn was also present.1 Although at least two historical accounts have been written about the Mexican Irish soldiers, for the most part, the general population of the United States is not aware of the Irish who fought for Mexico during the Mexican-American War. Few, outside of Mexico, have ever heard of the Irish soldiers who defected from the American lines and bravely fought defending Mexico from the American invasion. This is the story of the Batallón de San Patricio. For Mexicans, the men of the San Patricio Battalion will forever be enshrined in Mexico’s hall of honor.

The Mexican-American War of 1846-1848

The Mexican-American War lasted for two years, from 1846 until 1848. It resulted in 25,000 Mexican soldiers dead or wounded, according to the archives of the Mexico’s Secretariat of National Defense. Mexico also lost about 40% of its territory. The Americans suffered 17,423 dead or wounded and had over 9,000 soldiers go AWOL, according to American records. The war started as a result of the declaration of independence by the State of Texas in 1836 and the subsequent annexation of Texas into The United States in 1846. On May 11, 1846, U.S. President James K. Polk asked and received approval by Congress to declare war on Mexico. On May 13, 1846 the United States officially declared war.2 Although the perceived pretext for war was the Mexican insistence that Texas was not free to join the American Union, historians have generally accepted that the war was about the expansion of the American empire through Manifest Destiny.

As America prepared for war, thousands of European immigrants hit the American shores. Among these were the Irish who were fleeing the Great Hunger of 1845. With the offer of free acres of land and three months of advanced pay, many enlisted in the American army.

Unprecedented American Desertions

John Miller, in his book; “Shamrock and Sword” writes that the desertion rate for American forces was the highest during this conflict as compared to other wars. According to Miller, the rate was 8.3%, compared to 5.3% for World War II and 4.1% for the Vietnam War. All the other wars in which Americans participated came in at less then 2%.4 Peter Stevens, in his book; “The Rogue’s March: The Saint Patrick’s Battalion” wrote that no U.S. Army has ever encountered the problems of desertion that plagued Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfred Scott. He adds that of nearly 40,000 regulars, 5,331 deserted.

The Reasons for Deserting and Joining the Opposing Army

Very few historians have written about the San Patricios. There are two reasons for this, on the American side the war was unpopular and was ultimately over shadowed by the American Civil War. Besides the debate within the United States about the war, the high desertion rates from the American lines made the discussion of the war taboo within the American military. On the Mexican side, the loss of a substantial part of its territory and the ongoing civil strife within Mexico has left a lack of historical record for the war. Two authors have written two books about the Saint Patrick soldiers. They are Peter F. Stevens who wrote “The Rogue’s March: John Riley and the St. Patrick’s Battalion” and Robert Ryal Miller, author of “Shamrock and Sword, The Saint Patrick’s Battalion.”

Although they both discuss the high desertion rate of the American soldiers, they seem to be trying to minimize the actions of the American Army before the war started. Historians on both sides of the border have acknowledged that the Americans were intent on instigating war with Mexico through unprovoked crimes; such as rapes and plunder and especially the desecration of Catholic Churches in Texas, the disputed territory. Also, many immigrants in the American army not only felt discriminated upon 6 by their fellow soldiers but also could not accept the American provocation for war. They began to dissert and cross the river to join the Mexican army in defense of Mexico. From the moment of the first battle at Palo Alto on May 8, many of the deserters battled their former comrades. German Christopher Friedrich Wilhelm Zeh, who coincidently did not like Mexicans, wrote in his memoirs that the US Army was a multicultural group where one of every thousand was an immigrant. 7 By his own admission, Zeh was an educated immigrant who considered himself an aristocrat. Although the American Army was composed of recent immigrants, discrimination permeated through the ranks. Catholic prejudice 8 and harsh treatment by Anglo-American superiors and the use of extreme disciplinary measures such as flogging added to the reasons for the desertions from Taylor’s ranks.9 “Potato heads” as the Irish were commonly called were particularly singled out for harsh treatment. 10 Under these conditions the immigrants had no difficulty abandoning their army and joining the Mexican lines in defense of Mexico. Mexico was especially active in recruiting the deserters.

Mexican Recruitment Efforts

Mexico has historically recruited foreigners to fight in its ranks since its War of Independence. Although authors Miller and Stevens seem to make much of Mexico’s active recruitment of American soldiers into the Mexican lines, for Mexico this was not something new, it was part of its war tactics. Foreigners have continuously been welcomed into the Mexican military ranks. By the time the U.S.-Mexican War started, 16 foreigners had reached the rank of general in the Mexican army with many others serving in other capacities.

Throughout the war, Mexico actively recruited American soldiers to defect their lines and join the Mexican army. The German immigrant Zeh, serving in the US Army acknowledges in his memoirs that the Mexicans routinely passed out pamphlets directed at the American immigrant soldiers printed in German, English and French. According to Zeh, the pamphlets read; “We live in peace and friendship with nations you come from. Why do you want to fight against us? Come to us! We will welcome you as friends with open arms, take care of your needs, we offer you more than the Yankees can provide, due to their brazenness, we (sic) have been forced into this war. Join us and fight with us for our rights and for our sacred religion against this infidel enemy”. Zeh adds, “Several hundred Irishmen, stirred up by religious fanaticism, went over to the enemy, thanks to this piece of paper.”

To the Irish, the call for defending the motherland against invaders resonated among them as they remembered the Penal Times in their history. [1] They embraced the Mexican position that simple farmers were being attacked for their land and decided to join the Mexican ranks.

El Batallón de San Patricio

In October of 1846, after an additional 50 or so, American soldiers had deserted the American ranks, bringing the total number of deserters to about 100, 14 Santa Anna, using war powers bestowed upon him by the Mexican Congress directed that two infantry companies be formed. 15 The two companies would form the Batallón de San Patricio. Each company consisted of one captain, one lieutenant, two second lieutenants, one first sergeant, four sergeants, nine corporals, four cornets and eight soldiers. According to a dissertation by author Dennis Wynn, the battalionwas formed in October of 1846 as a separate unit. 16 Additionally, according to Mexican army payroll records for November 1846, “Voluntarios Irlandeses” were receiving pay from the Mexican government.

Although the San Patricio Battalion was made up predominantly of Irish immigrants, other European nationalities also comprised the element. 18 Of the 175 members of the San Patricio Battalion, 40 were from Ireland, 22 from the United States, 14 from the German States and the rest from other countries.

The Green Silk Banner

Although not in common use in smaller units, Santa Anna allowed the San Patricios to fly a war banner during the war. The green banner, made by peasants according to Mexican publications, had on one side a golden harp surmounted by the Mexican Coat of Arms with a scroll on which was painted "Libertad por la Republica Mexicana". Under the harp was the motto of "Erin go Bragh!" On the other side was a figure, made to represent St. Patrick, in his left hand a key and in his right a crook or staff resting upon a serpent. Underneath was added "San Patricio”. 20 No known existence of the flag exists today, although a couple of reproductions have been made.

John Riley

John Riley of K Company, 5th Infantry 21 deserted his American post and joined the Mexican ranks on April 12, 1846 22 prior to the US declaring war on Mexico. It is important to note that Riley defected the American ranks prior to the actual declaration of war, thus it was peace time when he abandoned the US Army. He is generally credited with organizing the Irish Battalion. Part of the confusion, over whether Riley organized the battalion is caused by the different spellings of his name found in official government records. John Riley, himself signed his name as Riley, other times as Riely, Reilly, or O’Riley in his correspondence to others. Mexican government records list him as Juan Reyle, Reley, Reely or Reily. His enlistment record for the U.S. Army lists him as Reilly.

On September 2, 1845, Riley enlisted for a five-year term at Fort Mackinac. He left for the Texas border two days later. During the last three weeks in March of 1846, Riley, under Taylor’s Army, setup camp in Texas, just across the river from Matamoros. On April 12, 1846, Riley obtained a pass from Captain Merrill to attend a Catholic Mass, deserted and joined the Mexican Army.

According to the records of the period, Sergeant John Riley’s ability was such that he was in line for a lieutenant’s commission although rising through the ranks during this period was difficult at best. 25 This discredits some of the misinformation put out by some publications of the period that attempted to suggest that Riley was a malcontent soldier. Although, some historians have argued that Riley did not actually form the San Patricio Battalion, the plaque in Mexico City commemorating their contribution to the war gives credit to Riley for the formation of the battalion. 26 By most general accounts, The San Patricios fought bravely throughout the war. The Battle of Buena Vista and Churubusco is where the battalion left its most notable war marks.

The Battle of Buena Vista

One of the most “vicious” battles of the war was the Battle of Buena Vista 27 fought on February 22 and 23 of 1847, near Saltillo. In this battle 4,759 Americans engaged about 15,000 Mexicans. Rather than a battle, it was a serious of fights with few positions changing hands; consequently it was at first difficult to tell who had won. 28 General Francisco Mejia’s Buena Vista Battle Report lauded the San Patricios’ “as worthy of the most consummate praise because the men fought with daring bravery.”

The Battle of Churubusco

On August 19 and 20 of 1847, Mexico suffered two devastating defeats, the second of which saw the destruction of the San Patricios as a unit in this war. 30 Of the original 120 San Patricios, 35 were killed in action and 85 were captured by American forces. 31 It is probable that most of the 40 unaccounted for Irish soldiers continued to fight in other elements of the Mexican Army until the end of the war. The thirty-five San Patricios’ killed in action included two second lieutenants, 4 sergeants, 6 corporals and 23 privates. 32 American losses in this battle were, 137 killed, 879 wounded and 40 were missing.

After the battle, the captured San Patricios were tried for desertion during war time and all were found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. Hanging was reserved for traitors. 34 According to President Zedillo’s speech honoring the memory of the Irish soldiers, more than 60 San Patricios were hanged, while ten were whipped and branded with the letter “D”. 35 Miller, on the other hand, reports in his book that under General Scott’s, General Orders 281 and 283, issued in the second week of September 1847, Scott upheld the capital punishment for 50 of the soldiers, pardoned five and reduced the sentences for the other fifteen. John Riley was included in the last fifteen because he had deserted during peace time and therefore could not receive the death penalty. 36 Riley had deserted prior to the official declaration of war.

Under orders of Winfield Scott, the last of the 50 San Patricios were hanged facing Chapultepec Castle precisely at the time the American flag was raised after the American victory during that battle. 37 The mass executions left a deep impression on the Mexican population. Rioting broke out in Toluca after the news reported that the executions had taken place. Mexicans intent on seeking revenge threatened to kill American prisoners but were prevented from doing so by the Mexican authorities. 38 From the Mexican point of view, the San Patricios should have been treated as prisoners of war, not criminals.

Instead of hanging, Scott ordered that the 15 San Patricios spared the death penalty, be instead branded with a two inch letter “D” for desertion with hot-iron on the right cheek and receive 50 lashes. It is unclear why three of the men were instead branded on the hip, rather than the face. These three were made to wear an eight pound iron collar with 3 one-foot long prongs each. 39 Scott also ordered that the San Patricios be imprisoned until the American army left Mexico. Upon being mustered out, Scott ordered that the men’s heads be shaved and drummed out of the Army. Although Scott intended to return the San Patricio men back to the United States at the conclusion of the war, the Mexican government prevailed in keeping them in Mexico.

The Mexican Government had called the punishments an act of barbarism, “improper in a civilized age.” 40 Under the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the San Patricio prisoners were to be left in Mexico. Mexico had insisted on this clause in the treaty during the negotiations. Maj. Gen. Butler issued General Orders 116 on June 1, 1848. In the last paragraph of that order, Butler ordered that; “The prisoners confined at the Citadel, known as the San Patricio prisoners, will be immediately discharged.” After the officer in charge of the Citadel read the orders, the 16 prisoners, including John Riley had their heads shaved, the buttons of their uniforms stripped off and marched out of the fortress while the bugler played “Rogue’s March”. 41 John Riley, instead of being branded once, was branded twice according to some of the reports of the time. The reports indicate that the double branding may have been a result of the first “D” being applied backwards, either intentionally or under orders. The second “D” was then applied correctly.

The Aftermath

It can be argued that the defense of your homeland is a duty all citizens must obey when an invading army threatens to destroy your country. Many heroes have emerged from the defense of their nations. No truer hero exists than those who give their lives for their adopted nation. Authors Miller and Stevens have made central to their position that the San Patricios deserved what punishment they received by the fact that they had deserted. They have pointed to the records of the Court Martial’s, provided by the American government, where the defense for some of the San Patricios was “drunkenness”. Thirty-seven had pleaded not guilty and twentyseven had pleaded drunkenness. Both authors seem to imply that the San Patricios did not abandon the American lines for religious or discrimination reasons because none relied on religion or maltreatment as a defense.

Author, Wynn points out in his dissertation the futility of offering abuse or religion as a defense under the Articles of War during that time. Wynn goes on to point out that because of the trouble the American army had in keeping its soldiers in their ranks, they had instituted a general order whereby drunken AWOL soldiers were allowed back into their units with minor punishment. 42 The San Patricios’ probably chose to mount a defense against the hangmen’s noose the best way possible under the conditions of the time. Knowing the futility of maltreatment as a defense they chose drunkenness.

Part of the reason for the lack of more concrete information regarding the San Patricios and the distortion of their reasons for disserting the American army may lie in that the whole affair was an embarrassment to the United States. Continued Catholic persecution in the United States after the war may have also contributed to the distorted record. “Some newspapers in San Francisco cite that affair to prove that Catholics are disloyal,” wrote a private citizen in a letter to the Assistant Adjutant General in 1896 requesting information on the San Patricios.

Because of sentiments against Catholicism and the harsh treatment by American forces of the San Patricios, the American Army seemed reluctant to discuss the affair publically. In 1915, the American War Department was finally forced to acknowledge the existence of the San Patricios and their treatment of them at the end of the war. Ordered by Congress in 1917 to turn over the records to the National Archives the army complied. The documents detailed one of the most embarrassing episodes for the American Army. 44 For the San Patricios, their story could finally be told truthfully for all to know what was true in their hearts.

After leaving prison, the remaining San Patricios rejoined the Mexican Army and continued to function as a unit for almost a year after the Americans left Mexico. 45 Riley was made commander of the two infantry companies with the brevet rank of Lieutenant Colonel, (2) although he was actually a Captain. One unit was tasked with sentry duty in Mexico City while the other was stationed in the suburbs of Guadalupe Hidalgo. 46 By late 1850, 20 of the original San Patricios left Mexico and returned to Ireland under the agreement Mexico had made with them when they enlisted to help them return should they choose to do so. 47 Riley was not among them.

Juan Reley

Although the two books, “The Rogue’s March: John Riley” and “Shamrock and Sword” erroneously states that John Riley disappeared into history, John Riley died on the last days of August 1850 and was buried in Veracruz under the name “Juan Reley”, the name under which he had enrolled into the Mexican Army. 48 Miller, in his book, “Shamrock and Sword” acknowledged that Riley mustered out of the Mexican army in 1850 at Veracruz but speculated that Riley had left on a ship bound for Ireland.

Remembering the Irish Soldiers in Mexico

Mexicans celebrate the Irish soldiers on two days, September 12 in honor of the anniversary of the first executions and on March 17, St. Patrick’s Day. Numerous street names across the country honor their contribution to the Mexican cause. In front of the Convent of Santa María in Churubusco the street is named “Mártires Irlandeses”, or Irish Martyrs.

The Mexican government has officially recognized the contribution of the San Patricios through official acts of government. In 1997, President Zedillo held a ceremony in honor of the 150th anniversary of their executions along with Ireland’s ambassador. 51 On Thursday, October 28, 2002 the LVII Mexican Congress held a ceremony where the inscription “Defensores de la Patria 1846-1848 y Batallón de San Patricio” or “Defenders of the Fatherland 1846-1848 and the San Patricio Battalion” was inscribed in gold letters on the Wall of Honor in the Chambers of the Congress. Three hundred and ninety-four Mexican congressmen, along with Irish Ambassador to Mexico, Art Agnew, attended the ceremony recognizing the sacrifices made by the young Irish soldiers.

In 1959, a plaque was erected in Mexico City commemorating the Irish Heroes of Mexico. 53 The inscription of the plaque reads, “To the memory of Captain John Riley of the Clifden area, founder and leader of the Saint Patrick’s Battalion and those men under his command who gave their lives for Mexico during the U.S.-Mexican War of 1846-1848.” 54 Mexican sculptor, Lorenzo Rafael, designed the plaque that is located in San Jacinto Plaza, now known as Villa Obregón. Finally, in early September of 1997, Ireland and Mexico jointly released two postage stamps in commemoration of the 150th Anniversary of the San Patricio Battalion. John Riley’s lawsuit against the US

Author, Fairfax Downy, in his 1955 article in the American Heritage Magazine perpetuates the often repeated myth that Riley “dared bring suit against the United States in Cincinnati in 1849 to recompense him for damages received in his flogging and branding.” According to the research conducted by Wynn, for his dissertation, there is no record in Cincinnati of this lawsuit ever being filed. Wynn contacted the courts directly.

Clifden 2012 would like to thank Martín for letting us reproduce his paper here.

The area of Clifden has been settled for at least 7,000 years, and possibly as far back as 10,000 years. This Age, known as the Mesolithic or middle Stone Age, was dominated by a hunter/gatherer lifestyle based on fishing, hunting of wild Boar ( the only large mammal in Ireland at the time) and fowling. Important evidence from this period came to light a number of years ago when a spearhead called a “Bann flake” was found by Jarlath Hession in top-soil he got from John Coneys’ farm in streamstown. More recently, a large kitchen midden (an ancient heap of rubbish) mostly Dogwhelk shells, was dated to between 6-7,000 years old. This midden is one of more than twenty from west Connemara and is located on the shore at Renvyle beach. This is one of only three sites dated to the Mesolithic Age on Irelands west coast. The remains of three such middens are to be found on the shores of Clifden bay, where they are dominated by oyster and periwinkle shells. Two lie opposite each other, one at the tip of faul, another at the shore at glenn Irene and a third recently discovered opposite the Clifden boathouse on the shore of Errislannann peninsula, in drinagh town land. These middens are undated and elsewhere in Connemara such middens have been dated to the bronze age 2,000 B.C. and the early christian times, 5th to the 10th century A.D. in the Errismore peninsula, south west of Clifden.

Closer to town, Velta Conneely’s keen eye discovered two beautiful polished stone axes while tending her garden on the edge of Clifden. These are very important finds and now are in the national museum and are evidence of early farming communities active in the Clifden valley between 5 and 6,000 years ago during the Neolithic or new Stone Age. These farming communities displaced the earlier hunter/gatherer and cleared the extensive mixed woodland that dominated the Connemara landscape at the time. These communities traded in stone axes and Connemara marble beads and built an extensive series of tombs throughout west and northwest Connemara. There are a number of such tombs in the environs of Clifden, but they’re extremely difficult to find. The first of these was shown to me by the late Kevin Stanley and is located at the base of a drumlin in Ardagh town land south of the town. This tomb still has its capstone intact. To the east of the town, in Couravoghil town land, the late Martin Coyne of Crocaheagla pointed out to me the remains of a beautiful tomb buried in the peat bog. Associated with the tomb are the remains of a pre bog wall, revealed by turf cutting. Similar ancient walls are to be found in the bogs between lough Auna and Shanaheever. These were shown to me by the late Nicholas Coyne. In the same area, Tom Joyce on whose land these sites were found, showed me the remains of an ancient trackway running into the lake. To the west of these, on Martin Coyne’s land, there is a small leaba agus gráinne, as these tombs are more commonly called “ag gob amach as an portach” overlooking the inner regions of Streamstown bay in letternoosh townland.

During the Bronze Age, these tombs go out of fashion around 2,000 B.C and are replaced in the landscape by less visible burials in stone cists or boxes, sometimes with a standing stone or stones above them. One of the standing stones around Clifden Castle is likely to be of Bronze Age date, the smallest one on the mound next to Henry O’Toole’s house and another possible one close to the Midden site on Faul townland, at the mouth of Clifden bay. Others occur, possibly the remains of a Stone circle, on Tom King’s land in Streamstown. In the hills northwest of the town, there is a beautiful hidden lake ”loch an Ime” and overlooking this lake, there is a long cist grave set in a low cairn. This site is covered in heather and was pointed out to me by my neighbour John Conneely and Gabriel Keady of Fakeeragh.

Another cairn of possible Bronze Age date is located in Tullyvoheen, behind one of the houses on the north side of the Clifden to Galway road. The sheltered valley, which envelopes the town of Clifden, with its rich flood plain and meandering river, would have been an attractive place to live in prehistoric times, though most of the structures were likely to have been built in timber rather than stone. Another recent discovery from the Clifden area was that of a Fulachta Fiadh (burnt mound) this site is located at the side of a small spring, on the south side of Clifden bay. It consists of a horseshoe shaped mound of burnt stone. The stones were exposed in the section face of a small path used by the horses from Errislannan manor. These sites were originally cooking sites where water was boiled in a stone or timber lined trough using baked stones from a nearby fire. Other examples of such sites are found overlooking Kingstown bay and there also found on the Island of shark, Boffin and Inislyon, off the northwest Connemara coast. The beautiful mountain valley of Gleann Glaoise, in the Maam Turk mountains, also contains a group of these sites in addition to a number of white quartz standing stones. Fulachta Fiadh generally date to around 1,000 B.C, but can be as early as 5,000 B.C.

The Bronze Age gave way to the Iron Age, sometime in 6th century B.C. though this is a shadowy period in Connemara’s pre-history. A number of sites however may be dated as far back as this, including the spectacular sited Cashel (stone fort) which controls the narrow neck of land overlooking Waterloo Bridge, above Joe O’Malley’s house. The nearby sub town land of Doonen may have got its name from this site. I found this site during a flight over Connemara with my good friend Marcus Casey many years ago. Connemara has relatively few Ring Forts and those that do exist tend to be in defensive positions like this one. On the coast at Fahey, there is a related type site, a coastal promintary fort, which I used to scramble over the ramparts as a young boy to go fishing for Gunner with the Conneely’s, our neighbours, off the cliffs below. Years later, I realised that that bank and ditch was in fact the ramparts of an Iron age fort. Good view of this site from the Scardaun carpark, on the Sky road.

These sites were used up to about the tenth century, and some of them would have had “Clochán’s” or bee-hive stone built cells. The name Clifden may have derived from one such “Clochán” or perhaps a standing stone and I like to think that the standing stone which abuts the corner of the ruined St. Mary’s church may in fact be the Clochán that gave Clifden its name. There are no early Christian church sites in the town, the nearest early site is at Kill, on the Errislannan peninsula. This site is named after St. Flannan. In the current graveyard at Ardbear, there’s a beautiful holy well, Tobair Beggan. Who Beggan was, is sadly lost, though there are over ninety holy wells in Connemara, the largest concentration in the whole country. The well tradition is dominated by the ecclesiastical giants of Colmcille and Macdara. Other lovely wells are associated with Cailín, Feichín Ceannach and not forgetting the great evangelical missionary who came to us from the crumbling world of late Roman Britain, Patrick the Briton. One of the more unusual finds from here are Roman coins found in a bog in Kylemore valley in 1826. They were coins of the emperor Diocletian. The great Lakeland region between Clifden and Connemara is scattered with a wonderful series of lake dwellings, many of which were discovered in the last thirty years, and two very important ones in 2010. One of these was found on Loch Dhúleitir by Ruari O’Neill, artist, guide and photographer, North of Carna. And another very large Crannóg (island Cashel) on Ross lake, near Moycullen.

In the Ninth century, the Con Maicne mara i.e, the dog sons of the sea, were attacked by pagan Vikings from the north. These Vikings never succeeded in establishing viable settlements in Connaught, however, Festy Price of Eryephort did find the remains of a Viking burial in the sands beneath his house following a great storm in the 1940’s. Apart from his long sword, shield and dagger, there was no lasting Viking presence, as the Conn maicne mara, a war like people, saw them off. The descendants of the Vikings however, the Normans, left a more lasting legacy in the region in the form of family names and one spectacular castle, “Caislan na circe”, hens castle on the Corrib near Maam. The most common of these Norman families who were successfully Gaelicsised include the Joyce’s, the Burke’s, the Welshes, the Barry’s, the Gibbon’s, the Guy’s, the Staunton’s, the Pryce’s, The Stanley’s, the De coursey’s . However, these and the original Connemara families, the Conneely’s, the Conroy’s, the Keeley’s, the O’Malley’s etc were dominated by the O’ Flaherty lords throughout the Middle Ages from their great castles at Ard, Bunowen, Doon, Renvyle and Ballinahinch. The O’Flaherty’s of Bunowen were particularly Warlike and from their maritime base, they dominated the coastal waters of Connemara and Aran. Exported from these shores in this period was a luxurious trade item called “Ambergris”, which is derived from the vomit of a sperm whale. It was used both as a medicine and a perfume, and continued to be collected in the 18th and 19th century. During the late 16th century, the great Spanish armada, defeated in the English channel by the English and the Dutch, sailed around Britain and Ireland on their way home September-October 1588. This defeat turned into a disaster, when the autumnal storms drove dozens of these ships on to Irelands west coast, including at least two on to Connemara’s coast. The survivors of these shipwrecks were mostly murdered and or handed over to the English for execution, by the O’Flaherty’s and the O’Malley’s, a small number ransomed, while some were held over, according to English complaints, for the use of the O’Flaherty lords It is unlikely that the swarthy good looks of the Connemara people come from inter marriage with the few Spanish armada survivors who managed to survive.

The wars of the 17th century saw the destruction of the Gaelic lords, and the confiscation of their lands by the state. Some lesser lords managed to hold on into the 18th century as middlemen and traders, but Gaelic culture continued its long decline. In the 18th century however, the ancient maritime skills of the Conn Maicne mara were put to good use when they were heavily involved in a lively, if illegal, two way trade of wool, wine, sherry and tobacco. Connemara became a byword for lawlessness. This trade, together with coastal fishing, which included the hunting of Basking Sharks, brought prosperity into every Cuan, from Cashla to the Killaries. The coast of Connemara is dotted with literly hundreds of small quays, wharfs and slips, though most of these are probably to do with local trade in Turf, Kelp and Poitín, Ardbear bay is particularly rich in such features, including a very large recently discovered quay located on the south shore of Clifden Bay, opposite the Clifden Boat club. Other good examples of large quays are to be found below Morris’ house at Ballinaboy and at rusheen na cara, close to the salt lake. On inner Clifden bay, a number of very simple boat nausts have been identified, which probably pre-date the establishment of the town in the early 19th century. The trade in wool, butter, wine and tobacco was gradually stamped out, with the establishment of Clifden and the building of a whole series of Coastguard stations, the largest concentration in the country, all along the Connemara coast. The inshore fisheries of Connemara would have been of huge importance to the survival of the Connemara people over thousands of years and the continuation of that tradition is wonderfully illustrated by the surviving usage of Curraghs by the descendants of the Island communities of Inisturk and Turbot. In April 2010, a complex of fish traps was identified on a series of tidal streams that flow from Loch An Saille on the Errislannan peninsula. This ancient way of fishing, using a Cohill (net) is an extraordinary survival. The traps were used to catch Marns, a small fish identified as Sand Smelt by Dr. James King. Mr. John Folan, who showed me how these traps were used, is one of the last practisioners of this ancient form of fishing, whose ancestry can be traced back almost 10,000 years. He has since built a replica Cohill for display in the National museum in Turlough house, Co. Mayo.

The Adventure to Clifden Featured

Breandán O’Scanaill traces the flight of Alcock and Brown and outlines the conditions prevailing in Clifden at the time.

On June 15th 1919, Alcock and Brown crash landed their Vickers Vimy aircraft in Derrygimla Bog just south of Clifden, after their harrowing sixteen hour flight from St. John’s, Newfoundland. An exciting new link had been forged between the old and the new world.

These two gallant RAF airmen, Capt. John Alcock and Lieut. Arthur Whitten-Brown, had set off from St. John’s the day before, Saturday June 14th in a two-seater bi-plane. This aircraft, a Vickers Vimy, had been designed to fly long range bombing missions, and a lot of modifications were needed for the attempt of the transatlantic flight, including doubling the flight endurance to twenty hours. Fuel capacity had to be increased to 865 gallons. It was powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines of 360 horse power each. After test flights in England the aircraft was dismantled and shipped to St. John’s, arriving there on May 26th. Then began the task of reassembly, which was hampered by bad weather, but once completed a number of test flights took place and the craft was declared ready to make the awesome journey.

The start of the flight was relatively trouble-free, apart from a prolonged take-off, but soon they ran into problems. Fog and cloud reduced visibility and Brown needed clear skies to navigate reliably. Still they pressed on. Next, the radio failed, and the starboard exhaust and silencer disintegrated making conversation impossible.

Weather conditions were also getting worse and the craft was thrown about. Battered by hail, both men feared that the aircraft’s fabric would be torn. Alcock lost his bearings at one stage and the plane went into a spin and fell 4,000ft Struggling to regain control, he succeeded in doing so just 50ft from the sea! As the rain turned to snow, the controls began to freeze up. On six occasions, Brown had to leave the cockpit and manually clear ice from critical parts of the aircraft.