An Early Tour Guide to Clifden

The following excerpt is taken from ‘Picturesque Ireland’ by John Savage, a well known Dublin born Fenian poet, journalist and author who emigrated to America in 1848. The work was first published in 1856; the version reproduced here is taken from an edition by Thomas Kelly Publishers of New York in 1877.

‘Picturesque Ireland’ is described as ‘a literary and artistic delineation of the natural scenery, remarkable places, historical antiquities, public buildings, ancient abbeys, towers, castles, and other romantic and attractive features of Ireland’.

Essentially, it was a handbook or travel guide to Ireland for the educated tourists of the time, published in the United States.

It paints a vivid and attractive picture of mid 19th century Clifden and the Connemara region for the reader, complete with illustrations.

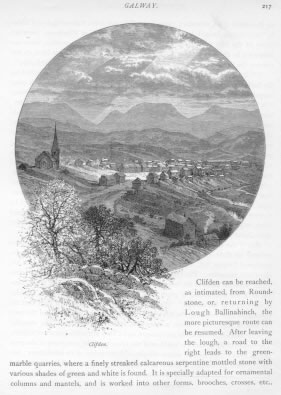

“Clifden can be reached, as intimated, from Roundstone, or, returning by Lough Ballinahinch, the more picturesque route can be resumed. After leaving the lough, a road to the right leads to the green-marble quarries, where a finely streaked calcareous serpentine mottled stone with various shades of green and white is found. It is specially adapted for ornamental columns and mantels, and is worked into other forms, brooches, crosses, etc. as souvenirs of a Connemara excursion. The ride from Ballinahinch to Clifden is “surprisingly beautiful!” and, to use again the words of Thackeray, there are views of the lake the surrounding country, which, in his opinion, were not surpassed by the best parts of Killarney, “although the Connemara lakes do not possess the advantage of wood, which belongs to the famous Kerry landscape.”

Clifden is romantically situated on a height at the head of and overlooking the harbour of Ardbear, an inlet of Clifden Bay; while on the other side it is overtopped by the mountains which form a splendid amphitheater in the background. “It has arisen something after the fashion of an American town,” says a writer; because in 1815, it had but one house, and in the course of forty years it could boast of having four hundred houses. Although a stretch of fancy to compare this growth with that of “an American town” it was a matter of historical and no ordinary gratification in Ireland. It was founded by Mr. D’Arcy, one of the great proprietors. He pointed out the advantages which would accrue to this remote neighbourhood of having a town and a sea-port so situated; and he offered leases forever, of a plot of ground for building, together with four acres of mountain land, at but a short distance from the proposed site of the town, at twenty-five shillings – about six dollars – per annum. This offer was most advantageous, even leaving out of account the benefit which would necessarily be conferred by a town in a district where the common necessaries of life had to be purchased thirty miles distant; and where there was no market, and no means of export for agricultural produce; and so the town of Clifden was founded and grew.

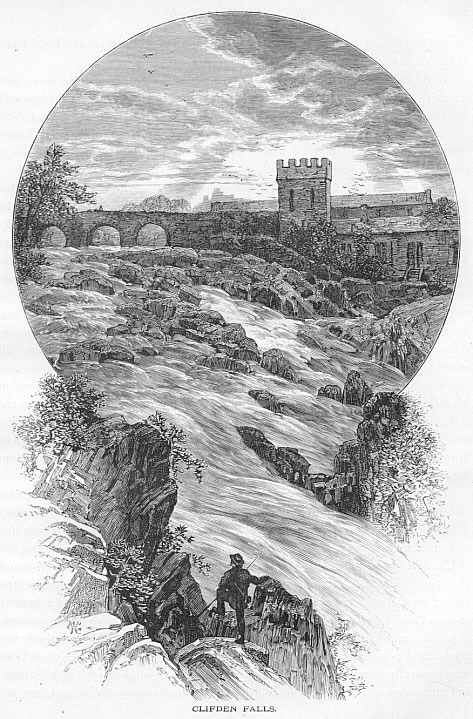

But if the town flourished, the founder did not. The D’Arcys “have been reduced by their liberality,” and, like the Martins, were sold out under the Incumbered Estates Act. The views of Clifden from the eminences around it are singularly attractive. The Owenglen River rushing down from Bennabola forms a fine waterfall close to the town; and the prison perched upon the rocky summit of a hill overlooking it, gives, says Black’s Guide, “in the distance, the idea of the Castle of Edinburgh.” We may, perhaps, agree with Hall, that the castellated form crowning a hill which rises between the Waterfall and the town presents a somewhat Spanish appearance. The waterfall is, without doubt, remarkably picturesque, and a very attractive feature of Clifden. The tumult of its cascades is heard amid the vivacity of the commerce of the prosperous town: “the rush of waters mingles with the voices of its inhabitants; yet, turning from the houses, it seems as lonely in its grandeur, as if in the center of the untrodden hills”. Rapidly flowing down from the Twelve Pins, the stream passing under an old-fashioned triple-arched bridge, which adds to the pictorial effect, suddenly turns at a right angle and leaps and shoots through a mass of rocks with very brilliant and fascinating effect. Reaching the bottom it takes another sudden turn, and dashes under another bridge, which spans its rocky borders, to join the Atlantic.

Nowhere is the facility for improving certain description of bog-lands more plainly and happily demonstrated than in the neighborhood of Clifden. Fine crops of grass, potatoes, and various kinds of grain are seen luxuriantly growing on land that was, not long in the past, only used for turf-cutting. As a harbour and sea-port, Clifden has important advantages; possessing deep water in the bay and safe anchorage for vessels of any burden. Many nautical men consider it the best harbor on the west coast for large vessels, and ships of war, when on service in the Atlantic, frequent it, where they ride out the fiercest gales in perfect security.

Clifden Castle, built by the former proprietor of the district and occupied by his successor Mr. Eyre, is less than two miles distant, beautifully situated on the shores of Ardbear Harbor, adorned with thriving plantations and grassy lawns, and commanding an extensive view south and east. A path, open to the public, runs along the bank of the bay from the town to the demesne, and affords the tourist a delightful walk. Willis thought these two miles “one of the most beautiful walks in Ireland;” and Inglis peremptorily says, “let no traveller be in this neighborhood without visiting Clifden Castle”. He is enthusiastic on the pleasure of this promenade, and his appreciation was enhanced by certain poetic surroundings of time and weather. “The walk from Clifden,” he writes, “by the water side, is perfectly lovely: and the distance not greater than two miles. The path runs close by the brink of a long narrow inlet of the sea, the banks of which on both sides, are rugged and precipitous. It was an evening of extraordinary beauty when I sauntered down this path; the tide was full, and the inlet brimful and calm; and beyond the narrow entrance of the bay lay in almost as glassy a calm, though with a gentle heaving, the wide waters of the Atlantic.

After reaching the entrance of the bay, and rounding a little promontory, Clifden Castle comes into view. It is a modern castellated house; not remarkable in itself, but in point of situation unrivaled. Mountain and wood rise behind; and a fine sloping lawn in front, reaches down to the beautiful land-locked bay; while to the right, the eye ranges over the oceans, until it mingles with the far and dim horizon. Twenty years ago, the whole of this was bog, now not a rood of bogland is to be seen. The lawn I saw laden with a magnificent crop of hay; while at the same time, the sunk fence showed a deep bog.”

Returning by the mountain road he was again delighted with the new views which this route disclosed, more Swiss in character than anything he had seen in Ireland. “The mountain range behind Clifden – the Twelve Pins of Bennabola – is always worthy of Switzerland. In its outline, nothing can be finer. Altogether I was greatly pleased with Clifden; and I think I may safely risk a prophecy, that this town will rapidly rise into importance.”

The first quarter of a century of its existence was a period of remarkable development, and if the succeeding period has not been as enterprising in the same ratio it was because of the slow rate of improvement in the interior. Its beauty and advantages are universally acknowledged, and Sir John Forbes pays it an additional recognition which, coming from a distinguished physician, will not be overlooked by invalids. After paying respect to “the majestic summits of the ever-charming Bennabola,” he continues: “From the high grounds in its vicinity there is a full view of the Atlantic; as well as of the innumerable seas-inlets that break through and inclasp the land on all sides with their glittering arms. There is indeed, something singularly pleasing in the landscape all around, particularly in that hilly ridge which looks along the Bay of Ardbear, and commands the view of the wide Atlantic beyond it. Although I hardly know in what the charm consists, I have certainly seen no spot in Ireland, which, from the attractiveness of mere locality, would claim my suffrage, as a place of residence, so entirely as Clifden. Over and above its scenic beauties, its position is such as to insure for it every terrestrial and climatorial condition that is found most conducive to health.”

The tract on which Clifden stands was formerly called Clochan or Cloughan, and it is still so called in the Irish, which means a beehive-shaped stone house. The modern is a corruption of the old name, the ch being changed to f, in this and other names of places, illustrations of which are given by Joyce. The hill of Cloughan-ard—the ascent of which is recommended for views of the town and vicinity—retains the original name. In connection with the old language, the author of A Run Through the West of Ireland who was in Clifden on a market day, and had a good opportunity of observing and speaking with the concourse of people who had all sorts of commodities for sale, says, “We found nearly the whole rural population speaking Irish. Throughout all our route we found Irish very generally spoken, and as in our previous tours through Wicklow, Killarney, and the south, my English wife heard English almost universally used, she entertained the notion that the Irish language had completely died out. This was removed by her trip to Connemara.”

Thanks to Gerritt Nuckton for transcription.