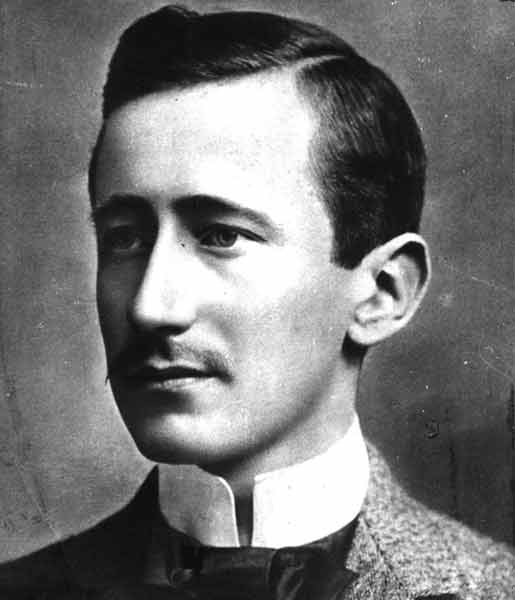

GUGLIELMO MARCONI (1874-1937)

“There have been three great moments in my life as an inventor. One when my early wireless signals rang a bell at the other side of the room in which I was carrying out my experiment; the second when the signals from my station at Poldhu in Cornwall found response in the telephone receiver I was holding to my ear at St. John’s, Newfoundland, 1800 miles away over the Atlantic; and today when I quietly contemplate the possibilities of the future and feel that my life’s work has provided a sure foundation on which the workers of today and tomorrow may build.”

[Guglielmo Marconi - December 1935]

The peaceful revolution of Radio, or wireless communication as it was once called radically changed society in the modern world. Guglielmo Marconi was the pioneer of this revolution: his system of wireless telegraphy which was developed in 1895 marked the beginning of Radio communications. Thanks to his extraordinary skill at combining outstanding technical know-how and business acumen, Marconi was able to dedicate his life to the development of his invention and gradually send his radio messages ever further afield.

The pioneering phase of Radio communications ended with the first transatlantic radiotelegraphic transmission at the beginning of the twentieth century. The opening of the Clifden station in October 1907 allowed Marconi to fulfil his most ambitious goal: the setting up of a regular communications bridge between the two shores of the Old Continent and the New.

Two years later, at the age of thirty five Marconi was awarded The Nobel Prize for Physics. Marconi was the living symbol of Radio communications and his extraordinary career lasted forty years, until death in Rome in 1937.

ABOUT GUGLIELMO MARCONI

Guglielmo Marconi was born in Bologna on 25th April 1874. His father, Giuseppe, was a rich landowner and his mother, Annie Jameson, was one of the four daughters of Andrew Jameson of County Wexford, the well-known and wealthy distiller of Jameson’s Irish whiskey. The young Marconi spent long periods in England and Tuscany with his mother and brother Alfonso and for this reason he didn’t regularly attend school. He had private lessons but preferred to cultivate his scientific interests. When he was 16 he set up a laboratory in the attic of his father’s house (Villa Griffone in Pontecchio near Bologna) where he started his first experiments with electricity.

In 1892 he embarked on his first important scientific project to try to design a new type of battery for the international competition, with a 2000 lire prize, promoted by the technical journal “L’Elettricità” to which he had a subscription.

Documents from the period, family papers and Marconi’s early notebooks, demonstrate the young aspiring inventor’s ambition and determination. Reading matter, his subscription to the illustrated weekly magazine “L’Elettricità”, documents regarding purchases of materials for experiments and private lessons in scientific subjects are all elements that paint a picture of the development of an “ardent amateur student of electricity” (as Marconi described himself in his first interview given in London in 1897) and that at the age of 20 lay the foundations for the beginning of radio communications. Indeed from 1894 he dedicated himself to developing the idea of using electromagnetic waves for “wireless” communication and with this objective in mind he worked even more intensely in his laboratory in Villa Griffone achieving important results the following year.

Following the discovery of electromagnetic waves by Heinrich Hertz in 1888, several European researchers investigated this new phenomenon. The most famous among them were Oliver Lodge, Edouard Branly and Augusto Righi. They carried out important experiments inside their laboratories, whereas Marconi took the waves outside his laboratory with the intention of transmitting signals over ever-greater distances.

In the summer of 1895 he succeeded in sending a signal to a distance of 2km. In those experiments the transmitter of Marconi’s first system of wireless telegraphy was placed in the garden of Villa Griffone and the receiver was on the other side of a natural obstacle, the Celestini Hill, which could be clearly seen from the window in his laboratory. The famous gun shot fired by one of Marconi’s assistants to confirm the reception of the signal demonstrated that the system could work even in the presence of natural obstacles. This initial success convinced the young inventor of the potential of radiotelegraphy and to develop this potential he decided, in agreement with his family, to move to London.

On various occasions Marconi denied the presumed indifference of the Italian authorities to his invention, explaining that it was a natural choice for his family to move to England due to the family connections he knew he could count on in what was the most advanced industrialised nation of the period. This information which had circulated with a certain persistence has remained part of the legend created around Marconi. Due to their activities the Jamesons had strong ties with important groups of London entrepreneurs. In particular Henry Jameson Davis, an engineer specialised in the design of windmills, was intrigued by his young cousin’s wireless equipment and believed that it was vital to present it to the right people.

In February 1896 Marconi moved to England and with the support of his Irish relatives (especially Henry Jameson Davis), he followed two important objectives: to ensure that his invention received legal and scientific recognition and to find the best conditions to exploit his radiotelegraphy system commercially.

Among his first contacts, and of extreme importance, was that with William Preece, the powerful Chief Engineer of the General Post Office, who after the first meeting with the young inventor, offered to Marconi the support of the GPO, in terms of physical facilities and technical assistance. Moreover, in September and in December of the same year Preece gave the first public presentations of Marconi’s invention: these events were widely reported and commented on in many newspapers and technical magazines.

In the same year Marconi filed the world’s first patent application for a system of wireless telegraphy (under the title “Improvements in Transmitting Electrical Impulses and Signals, and in Apparatus Therefore”). The complete specification was submitted in March 1897, and it was accepted three months later. This was a fundamental step and he was helped by the best patent agents available at the time.

In July 1897 the patent was transferred to the newly established The Wireless Telegraphy and Signal Company (later to be renamed Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Co.). Marconi was appointed the technical director, and together with Jameson Davis he secured control of the majority of the shares.

Seven of the new partners of the Company were Irish corn merchants. This confirmed the importance of the inventor’s family contacts. Although this line of business did not involve advanced, electricity related technologies, it was certainly dependent on fast and reliable systems of communication.

Marconi’s wireless telegraphy certainly was expected to follow that direction.

The Royal St George Yacht Club in Kingstown (now Dùn Laoghaire) was due to hold its annual regatta in July 1898 and the Dublin Daily Express and his sister paper Evening Mail decided to commemorate the centenary of the latter by reporting the yachting results by wireless – the very first of its kind.

During the Kingstown regatta (July 20-22nd, 1898) Marconi was on a tugboat to monitor the yacht races and sent wireless messages back to the harbour (where he had installed his land station) and from there they were decoded and forwarded by telephone to the Dublin newspapers for publication. During the two-day event more than 700 messages were transmitted across distances ranging from 16 to 40 km in order to give the newspaper information on the progress and the result of each race well ahead of its rivals.

It became what many believe to have been the first ‘live’ transmission of a sporting event in the world: it was a spectacular success and established Marconi as the leading figure in this new field of commercial communications.

During this period Marconi and his collaborators had to solve numerous technical problems especially the problem of interference between two stations that were working simultaneously. The problem regarding tuning was at least partially resolved when in 1900 the Marconi Wireless Company patented a device, even though the tuning problems continued for years.

Marconi’s main objective was above all to increase the distance of communication. During the summer of 1897 the transmissions reached 18 km. Then in 1899 they first reached 50km (in the first radio telegraphic transmission across the Channel). Marconi then exceeded 100 km (between equipment installed on the liner ship St. Paul and the Needles station on the Island of Wight). The distance was tripled at the beginning of 1901 (from Niton on the Isle of Wight to the Lizard Station, in Cornwall), and was farther increased in June (360 km, from Poldhu in Cornwall to the Crookhaven station, in the extreme south-west tip of Ireland). That same year was to prove really extraordinary for the 27–year-old inventor of wireless telegraphy.

Before the invention of radiotelegraphy ships were isolated at sea. The first fundamental use of Marconi’s invention was at sea. Marconi Radio Officers first went to sea in merchant ships in 1900 and for almost a century they provided the vital link between ship and shore.

Over the years the number of people saved at sea due to radiotelegraphy increased remarkably. In January 1909, for example, all the passengers and crew (over 1500) on board the Liner Republic which was shipwrecked off the North American coast were saved.

The most famous episode was that of the Titanic in April 1912. Among the victims of the disaster (about1500) was Jack Phillips, the senior radio operator, who was twenty-six years old and had already served on a number of liners as well as at the Clifden station. Those who survived (just over seven hundred) owed their lives to the wireless distress calls sent by Phillips. Among the many CQD and SOS messages that were sent was the sad confirmation sent by Phillips to his friend Harold Cottam, the operator on the Carpathia: “Yes. It’s a CQD, old man. We have hit a berg and we are sinking.” (The CQD message was still used by the Marconi Company Operators as a distress signal) .

These dramatic episodes aroused a great deal of interest in the media of the period and lead to a notable increase in marine radio services across the world.

Another distinctive episode linked to the use of wireless telegraphy at sea hit the front pages of the newspapers in July 1910 after the dramatic arrest of the notorious murderer Dr Crippen, and his mistress Ethel Le Neve, following a wireless message from SS Montrose to Scotland Yard. In one of the many newspaper comments wireless telegraphy was called “the invisible agent”. The role played by Marconi wireless in Dr Crippen’s arrest was a sensation, certainly another triumph for the new technology.

The passage from Radio telegraphic transmissions to Radio broadcasting was possible thanks to the advances in amplification techniques developed by the Englishman John Ambrose Fleming (inventor of diode valve in 1904), and the American Lee De Forest (inventor of the audion – triode valve in 1906). These techniques revolutionized Radio communications in the first half of the twentieth century, making broadcasting possible and later becoming essential for radio and radar systems, television and telephones until the advent of the transistor in 1948.

It was Reginald Aubrey Fessenden who, in 1906, performed the first Radiotelephony experiments by sending waves into the ether that were no longer only Morse code signals but complete sound signals. In the following years several technical devices were produced in this new field and, at the end of the World War I, all the components which were to make broadcasting possible were already in existence. An important moment was the transmission of the first Radiobroadcast concert, performed by the famous soprano Dame Nellie Melba on 15 June 1920, from the Marconi station in Chelmsford.

During the 1920’s broadcasting developed quickly and the radio as a means of mass communication came into being. The English BBC was born in 1922, and the first great American companies such as NBC and CBS were created. During those years Marconi kept up his experimental activity which produced important results for the new fields of Radio communications. Part of his experimental work in the 1920’s and the early thirties was carried out on board the yacht Elettra which he had bought in 1919. The Elettra was often Marconi’s floating home and laboratory, and was witness to many important experiments concerning short waves and from 1931, micro waves.

Marconi’s success in long distance communication was based on the use of ever longer waves. However, during World War I he returned to the investigation of short waves, which he had used in his first experiments, and recognized their possible advantages, showing once again his flexibility and pragmatism.

Marconi’s long career was suddenly interrupted, ended by his death in Rome on 20th July 1937. A two-minute silence of wireless stations throughout the world was observed as a fitting tribute to his massive contribution in conquering the airwaves. In those two minutes the ether returned to silence as it was before Marconi’s invention. It was an extraordinary tribute to commemorate a career studded with a host of awards, honours and scientific acknowledgements. Among these, 16 honours degrees received from famous universities among them Oxford, Cambridge and Bologna, his native city. His most famous award was that of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1909, shared with the German scientist Karl Ferdinand Braun, which was awarded “in recognition for their contribution to the development of wireless telegraphy.” He was the first Italian to receive it. Although Marconi was only 35, his name had often been mentioned in the previous years as a possible candidate for the Nobel Prize. In the solemn award ceremony Marconi held a conference at the Royal Academy of Sciences in Stockholm entitled “Wireless Telegraphic Communication”.

Marconi was invited to many countries across the world to illustrate the development of radio communications of which he became the living symbol. Among the numerous speeches given by Marconi during his 40-year career the one that can be considered to be his extraordinary scientific testament is the text of a radio message sent from Rome to Chicago in March 1937:

We have now reached a stage in the science and art of radio communications, when the expression of our thoughts can almost instantaneously and simultaneously be transmitted to and received by our fellowmen practically in every spot of the globe where a simple receiving apparatus is available [...]

Broadcasting, however, with all the importance it has attained, and the wide, unexplored fields still lying open to it, is not - in my opinion - the most significant part of modern communications, in so far as it is a “one way” communication. A far greater importance attaches, in my opinion, to the possibility afforded by radio of exchanging communications wherever the correspondents may be situated: whether in mid-ocean, or on the ice pack of the pole, or in the waste of a desert, or above the clouds in a airplane! [...]

In radio we have a fitting tool for bringing the people of the world together, for letting their voices be heard, their needs and aspirations be manifested. The significance of this modern means of communication is thus fully revealed: a wide channel for the improvement of our mutual relations is available to us; we have only to follow its course in a spirit of tolerance and sympathy, solicitous of exploiting the achievements of science and human ingenuity for the common well. I am firmly convinced of the possibility of realising this ideal [...]