From Connemara to Coomooroo and beyond (with a few places in between)

John Mannion, Australia.

I will probably never know what my paternal, great, great grandfather, Michael Mannion, his wife Mary and their infant son, John Francis Mannion thought as they looked back at the shores of Ireland in c1865 aboard a sailing ship ultimately bound for Australia. Michael Mannion was one of a family of five.

As Thomas Keneally said of his Irish ancestors in his 1991 book: Now and in Time to Be: Ireland and the Irish.

"... did they look back from the deck of whatever class they sailed in with a frightful grief, or with a mix of wistfulness and exaltation? Was their young blood really geared up for the longest possible dosage of sea then available to them? Did they think they'd be back to the dear, familiar sights and faces so often invoked in songs of emigration?

I'm sayin' farewell to the land of my birth

And the homes that I know so well,

And the mountains grand of my own native land,

I'm biddin' them all adieu . . .

On the other hand, were they pleased to see the last of it: the tribalism, the recurrent want, the contumely of being one of Britain's sub-races? Or did they harbour both sets of feelings? "

In any event that day was the last they would ever see of Ireland and possibly their three other children Mary aged seven, Bartholomew (my great-grandfather) aged five and Joseph aged three, whom they left behind, to follow several years later in 1873. Whatever their circumstances they must have been desperate to migrate to a new life, for not only was this a physical migration, it was a migration of their hopes and aspirations to re-establish and better themselves in the province of South Australia, 12,000 miles away.

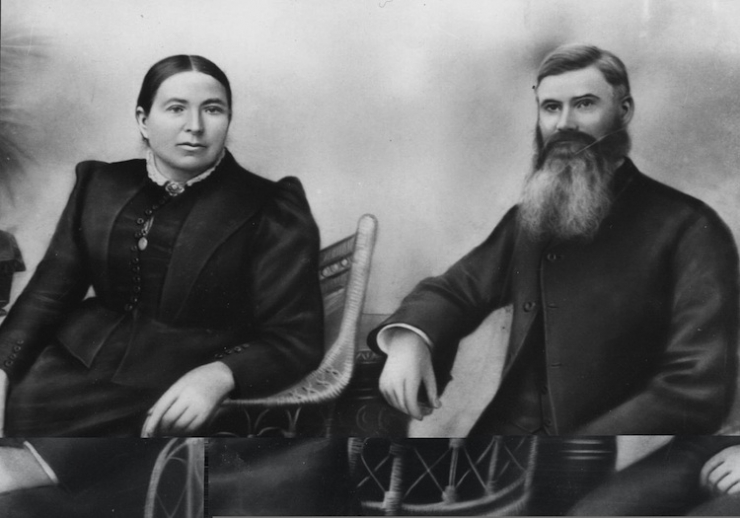

For many years it had been accepted in the Mannion family that, "Michael Mannion and Mary Coyne were married on 6 June, 1858. They came from Clifden, Ireland via the Cape of Good Hope arriving in Australia in 1871. They first settled in Farrell's Flat then Mannanarie and finally Coomooroo. When they came to Australia, they left three of their children in Ireland, namely Bartholomew, Mary and Joe, who came out later on."

This information was supplied by my great-uncle Joseph William Mannion and his sister Margaret Quinn, and no-one had ever queried it until I began some 'serious' research in 1997 and when I began researching birth dates and places, I found that three out of their seven "Australian-born" children were born prior to 1871. They may have been staunch Catholics but even their faith could not transport their unborn children across the ocean to South Australia!

Despite years of research, including a trip back to Ireland and to the United States, where I became acquainted with many 'cousin's', I have been unable to find out when and where Michael and Mary sailed from nor can I find any official record of their marriage. However I did visit the ruins of the family home a few miles east of the town of Clifden, nestled in a valley among the Twelve Bens east of Canal Stage and had a drink of water from 'Mannion's bog' (a rock-hole fed by spring water) in May 1986. On my visit in 1999, the rock hole had dried up and was only a muddy hole. This land is now farmed by Pauric Hynes who breeds Connemara Ponies, exporting several to Australia.

A neighbour of Pauric's, 'Paddy Pat Joyce' lives in a small cottage about half a mile away and I was told by a bloke in Clifden named Casey (his daughter has a chemist shop in Clifden) that 'Paddy Pat' was a local historian. On the first visit he wasn't home, but next day he was. It turned out that I'd met him in 1986, because after we got talking he said that an Australian called in a few years previous enquiring about the Mannion family and how they were married in 1858 by Fr O'Dwyer. Now there was no way that he could have known that from anyone else. He also said that if I'd been there 20 minutes earlier, I'd have met a Stephen King from Glasgow who was also seeking info on the Mannion family.

Paddy Joyce was an interesting old bloke, about 70 I'd say. He lived on his own in his cottage with no electricity, no telephone and no motor car. He had a battery radio, gas lighting and a bicycle, and a couple of sheep dogs for company. The old dog 'Swim' lived in the house with him. Paddy spoke very loud Nell reckons and was very philosophical about life, with many sayings.

When and where they arrived in South Australia, I have been unable to establish as yet. (Family records again indicate: Michael Mannion and Mary Coyne, second eldest daughter of Michael and Miriam Coyne of "Ilane Earaugh" Galway, Ireland, were married on 6 June, 1858 at "Killeen" in the presence of Darby Coyne and Penelope Coyne, County Galway, Ireland, by Rev. Fr. A. O'Dwyer.) When I was in Ireland in August 1999 I visited the Catholic priest at Carna, Fr Pauric Addley and had a look through the Parish records with him.(Nell was with me but she preferred to sit in the car and read!) Father Pauric was not entirely forthcoming with information until I mentioned 'Ilane Earaugh' and then it clicked! He told me that 'Ilane' is Irish for island (Oilean) and Earaugh was a small island off the west coast in the vicinity of Carna. At first Fr Pauric assumed that I was American; he was sick of American tourists not knowing anything about their family history arriving and expecting him to have all the answers! So I went away with a bit more knowledge. On the way back to Clifden we called in and had a look at one of the many roadside grotto's or shrines in the area. I noticed a bloke shifting some sheep in a nearby paddock, so we wandered over and had a yarn with him, mentioning that I was researching the Mannion and Coyne families. It turned out that he was typical of many Irish who lived and worked in New York, but intended to retire in Ireland, where he was building a house. However he told me to go back along the road and see a bloke by the name of Michael Coyne. So back we went only a few hundred yards, Michael Coyne was not at home, but his wife Margaret said he would be back soon so we waited. The Irish are very hospitable and we talked and had a coffee until Michael returned. Michael Coyne was actually born on Ilane Earaugh in 1918. His grandfather John Coyne was known as 'Lord of the Island'.

I have been able to follow their movements northward from Adelaide to Farrell's Flat, Hill River, Yongala and eventually Coomooroo, in c1876 from the birth records of their children.

Along the way seven more children were born:-

Michael Joseph Mannion, born 28 June, 1866, at Farrell's Flat, district of Clare, S.A.

Patrick Peter Mannion, born 28 August, 1868, at Farrell's Flat, District of Clare, S.A.

James Mannion, born 22 August, 1870, at Hill River, District of Clare, S.A.

Annie Mannion, born 3 September, 1872, at Farrell's Flat, District of Clare, S.A.

Martin Henry Mannion, born 18 June, 1874, at Farrell's Flat, District of Clare, S.A.

Bridget Mannion, born 6 July, 1876, at Yongala, District of Frome, S.A.

Edward Mannion, born 4 April, 1879, at Coomooroo, District of Frome, S.A.

(Note: Place of registration may be birth place or residence of parent/informant) This is an important note, as on Patrick Mannion's Death Certificate, his birthplace is stated as being Adelaide, South Australia.

From shipping records and newspaper reports, Mary aged 14, Bartholomew aged 11 and Joseph Mannion aged 9, arrived in South Australia at Port Adelaide aboard the sailing ship Asterope, from London on 30 October, 1873 accompanied by a Mr. John McDonough (aged 35). They had spent three months at sea and were classed as assisted immigrants. There were only twelve passengers aboard the Asterope.

John McDonough is still a 'mystery man', but may have been a relative; anyway, it can be assumed that these children joined their parents and five siblings at Farrell's Flat in 1873. I have been unable to find any official records of the births of Mary, Bartholomew or Joseph, only family records, but a John Manion is recorded as being born on 3 July, 1864, (0431) in the Lettermore District, Galway, Ireland to Michael Manion and Mary Coyne.

From information supplied on the South Australian birth certificates, Michael's occupations are listed as a farmer at Farrell's Flat in 1866, a shepherd at Farrell's Flat in 1868, occupation not listed at nearby Hill River in 1870, and from then on as a farmer at Farrell's Flat and Yongala in 1876. There are no land titles issued under Michael Mannion until 1876 at Coomooroo, so it can be assumed that he leased land in the various districts until then.

The 1860s was not a good decade for South Australian farmers, there were a number of factors responsible for this, such as the severe drought in the middle of the decade followed by a devastating outbreak of rust in the wheat crops. But increasing difficulty in obtaining new areas of readily arable farmland, coupled with the lure of country being made available across the border in the Victorian Wimmera district were causing intending farmers and farmers wanting larger blocks, to look interstate.

One of the major inhibiting factors to agricultural expansion was the 'cordon of pastoral country' which had been taken up and held by wealthy land owners under the original purchasing scheme............. Thus the state turned its attention increasingly during the 1860s to the problem of facilitating closer settlement and to finding more land suitable for agriculture.

The small farmer was always at a disadvantage as, under the South Australian scheme, land had to be sold at auction, and it had to be bought for cash and the small farmer found cash hard to come by. The Premier Henry Strangways proposed increasing the maximum acreage allowable to a sole purchaser from 80 acres to 640 acres and also abandoning the auction system in favour of a purchasing system by application at a fixed price and abolishing the cash payment by introducing a credit scheme for farmland buyers.(The Strangways Act)

Following the drought of 1864-66, the Surveyor General, George Woodroffe Goyder, was sent by the S.A. Govt. to assess the effects of the drought, with a view to allowing Government relief to pastoralists. Thus was drawn on the map, the famous "Goyders Line". The pressure for more land for farming increased with a run of good years in the early 1870s. Until this time, the Government had accepted Goyder's line to be the limits where farming should extend, but on 26 November, 1874 an Act was passed which permitted credit selection on all unappropriated lands 'situated south of the twenty-sixth parallel of south latitude'. This meant that the whole of the state was made available for farming!

The 'Strangways Act ' of 30 Jan. 1869 was originally designed to put the small farmer on his own land and by 1880 this had been achieved, however some including Goyder foresaw the disaster that would follow the farming of the more arid parts of the state, but their voices were drowned by those who considered that everyone was entitled to a share of the public estate, including Michael Mannion.

The Hundred of Coomooroo, in the County of Dalhousie was proclaimed on 8 July 1875. Michael Mannion selected Section 88, Hd. Of Coomooroo on 30 May 1876 and paid £1/acre for his land. The 565 acre property was on rising ground, about three miles north-east by road from the small township of Morchard, about 160 miles north of the South Australian capital, Adelaide and they named it Fair View. Although Michael Mannion was allocated Sec. 88, Hd. of Coomooroo of 565 acres on May 30th 1876, the Land Grant was not issued until April 3 1882, when paid for: £565. Part of the house they built in 1877 is still standing, as is a small one-roomed hut built in 1880, but apparently they did not establish the place all alone.

Records indicate that Michael's brother, Martin, a farm labourer, accompanied by his son, Patrick, and daughter, Rose arrived in the Colony in 1879 aboard the ship Woodlark. From Coomooroo School records, Rose attended the nearby school with her cousins and Michael Snr was named as parent. What happened to Martin and Patrick no one knows! but Rose stayed in S.A. with her cousins and eventually married and raised a family of her own, a descendant of Rose's, Jan Perry is currently researching her Mannion connections too, so we keep in touch. Another mystery are the 'O'Toole' family, more cousins of Michael Snr, whom he sponsored to come out to South Australia, and apparently they lived and worked at Fair View as well, before moving to the Port Pirie area.

The land in the Hundred of Coomooroo is situated outside 'Goyder's Line' of ten inch rainfall and for an Irish farmer and his family to start farming, literally from 'scratch' in this newly opened area, it must have taken a tremendous amount of faith. Farming is a gamble, there are elements of risks in farming and even with good farm management it still takes faith to go out in the late autumn weeks and sow a crop, believing that the rains will come and provide a harvest at the end of the year. That faith has been severely tested throughout the years, not only faith in their own ability and self-reliance, but faith in their Catholic beliefs and the Mannion's prospered at Coomooroo in the run of 'good years' during the 1880's and in 1884 bought out their southern neighbours property (Section 66, Hd. Coomooroo) of 440 acres for £517

Only one more child was born to Mary Mannion; Edward, on 4 April, 1879 at Coomooroo, unfortunately he died in infancy less than a year later, on 20 January, 1880 and his burial was the first in the Morchard Cemetery on 21 January, 1880, the Ceremony being conducted by the Catholic Priest, Rev. Fr. William Unsworth, a young Englishman. The Mannion boys were noted as being keen cricketers and horsemen, and on Sundays after attending mass at the Coomooroo Catholic Church/School, just down the road, friends and neighbours of the Mannion's would gather at Fair View for lunch in the large kitchen (12 ft. by 17ft.). After lunch they would play cricket 'out on the flat' and adjourn for tea, after which the kitchen was cleared and they would dance the night away.

Michael Snr, was an early councillor on the Orroroo District Council (est. Dec.1887) representing Coomooroo Ward in 1888/89, (when the Ward system was introduced ) 1890/91 and 1891/92.

Having a number of boys (7), Michael and Mary 'had' to find properties for them, so they purchased or leased various properties; one at Erskine, east of Orroroo; Matawoolunga, east of Yednalue; Uroonda, south of Cradock, Kanyaka Station, south-west of Hawker and Pat managed the Kanyaka Station and had an interest in the property at Uroonda as well, before eventually going to Western Australia, as did Bridget and Jack (John), while Martin studied engineering and went to Broken Hill as a mining engineer and Annie went to Broken Hill as well. Michael (Mick) Mannion Jnr. is also listed as owning land west of Coomooroo, in 1888, in the adjoining Hundred of Pinda, (Sect. 14, Hd. of Pinda, 606 acres) He increased his holding after buying the adjoining farm from his sister Mary, following the death of her husband, John Bourke in 1895 (Sect. 13, Hd. of Pinda, 593 acres).

Joseph and Bartholomew went north to Uroonda and settled at the 302 acre property they called Clifden (Section 142, Hd of Uroonda, County of Granville) which their father, Michael had selected in 1878, in recognition of their homelands around Clifden, Connemara, County Galway on the west coast of Ireland. They built a stone cottage and established a farm under what must have been very harsh conditions, but I guess all things are relative and they didn't know anything else! The original house at Clifden was four- roomed, two stone and two pine and daub, but as times improved it was re-modelled in stone with a cement tank adjacent.

During the severe droughts of the 1890's dust storms ravaged the district and stock died from lack of feed and water. Very little wheat was grown for the next ten years and during 1897 the State Treasurer provided seed wheat to District Councils; to supply to farmers for sowing in that year. At a Special Meeting of The District council of Orroroo, held on 9 January, 1897, re Seed Wheat Distribution many applications were considered including: Mannion M. 250 Bushels. Sec 66 & 88, Coomooroo. 1002 Acres, the application was granted, but the season was a failure and at a Special Meeting in Jan. 1898, M. Mannion along with 50 other farmers, was granted an extension of twelve months for the payment of Seed Wheat supplied. In Jan. 1899 Michael Mannion, along with scores of other farmers in the Orroroo district, was again granted an "Extension of time for payment of Seed Wheat."

Mary Mannion, a woman, not a super-woman, who had followed her husband, confronted the loneliness and the remoteness of South Australia, and bought up their family under harsh and difficult conditions, died at Fair View on 5 November, 1899 aged 63 years after a lengthy illness and from her obituaries in local and state papers, it is obvious that the Mannion's were a well known and respected family in the Coomooroo district. In Jan. 1900, Michael was granted another extension to pay for Seed Wheat and I reckon his faith would be sorely tested by now! with years of bad seasons, followed by the death of his wife. Along with many other pioneers who ventured north into this country to grow wheat, unaware that the average rainfall made it unsuitable for that venture, and through no fault of his own, after spending the most productive (and reproductive) years of his life trying to do so, he was forced to quit.

On 24 Feb. 1900, The D.C. of Orroroo received a cheque from The Queensland Mortgage Co. for M. Mannion's Seed Wheat (amount not noted) and on 11 Nov. 1902, Michael Mannion transferred Section 88, Hd Coomooroo to the Queensland Investment and Land Mortgage Co. The drought had broken him and I doubt that he ever recovered from the loss and grief of that tragedy, he obviously stayed on at Fair View, but in what capacity, I don't know? and as if that wasn't enough, a rabbit plague was infesting the district as well!

From the Minutes Book; Orroroo Council Meeting:- 28 May, 1904:

Letter re. rates, James McKenna on Mannion Land Section 66, 88 (Hd. Coomooroo) I dont' know the significance of this entry, but it would appear that a James McKenna, whoever he was, was responsible for the rates on Fair View. There is no further reference to the matter.

Michael stayed on at the farm, perhaps in forced semi-retirement, whilst son James ran the farm until his father's death on 29 June, 1904, aged 76 years. His obituary reads :

"On Wednesday, Michael Mannion an old resident of Coomooroo died. He was a large farmer and worked hard before retirement. His losses in stock and crops since 1895 had been heavy which affected him severely. He had a long illness and for a long time had been unable to lie in bed, owing to heart trouble."

Michael, Mary and Edward Mannion are all buried in an unmarked grave at Morchard Cemetery, although the plot is fenced by a cast-iron surround.

Following the death of his father, James stayed on at Fair View until 1909, when he left the district, and tavelled around the state, farming at Booborowie Experimental Farm, Waikerie, and eventually died in Adelaide and was buried in West Tce. Cemetery.

Bartholomew Bernard Mannion and Mary Teresa Neylon were married on 9 May 1887 by Father Bernard Nevin in the Cradock Catholic Church, in the presence of John Mannion and Annie Neylon. The Neylon family moved to Uroonda in 1881, from Kapunda and they tried farming in the vicinity of the Uroonda School with about as much success as their neighbours (Goyder's predictions were correct!) Clifden, in the Uroonda district, 8 miles south of the Township of Cradock was to be the home of Bartholomew and Mary and their ten children :

Annie Immaculate Mannion, born at home, 23 March, 1888. (Married John Fahey of Jamestown, two descendants)

Mary Catherine Mannion, born at home, 7 August, 1889. (Never married)

Michael James Mannion, born at home, 7 December, 1890. (Never married)

Martin Vincent Mannion, born at home, 7 August, 1892. (Never married)

Nellie Jane Mannion, born at home, 21 August, 1894. (Never married)

Bartholomew Coyne Mannion, born at home, 20 July,1896. (Never married)

Joseph William Mannion, born at home, 21 July. 1898. (Married Marie Kavanagh, no children)

Peter Laurence Mannion,born at Hawker, 16 May, 1900. (Married Eileen Williams, five descendants)

Patrick John Francis Mannion, born at Hawker, 4 April, 1902. (Married Mary Murphy of Jamestown, no children)

Margaret Doreen Mannion, born at Hawker, 25 July, 1906. (Married John Quinn of Mt. Bryan, five descendants)

The Mannion's and Neylon's endured the harsh seasonal and living conditions, possibly through their their frugal living and life-style and watched many of their friends and neighbours leave the area. ''Farmers who took up land outside of Goyder's Line were meeting with increasing difficulties, and nearly every year there were ammendments to Govt. Acts to try and give relief to these farmers; by 1882 many had walked off their properties."

In 1911, the Mannion's purchased a mixed farming property in a more reliable rainfall district at Willalo, in the Booborowie district, north-west of Burra and about 120 miles south of Cradock and in 1913-14, some of the family headed south to greener pastures. All of the Mannion children, except Margaret who was not of school age when the family moved to Willalo, attended the Uroonda School/Church, five and a half miles north-east of their home, and completed their schooling at Willalo School. Despite the area being settled after 1910, the Mannion's were among the earliest at Willalo and established themselves in a small galvanised iron house of 4 rooms. Being in a very productive area, farming must have paid off, as in around 1920 they had a stone house constructed, and in 1929 a verandah and main bedroom were added to the front and 'a priests room' built onto the back. A stone implement shed also functioned as a shearing shed and at shearing time all the farm machinery was removed. Hillside, was to be the focus of many family functions due to it's central location in the state and Bartholomew used to put on a 'keg' on the front verandah at Christmas. My father has childhood memories at Hillside and recalls playing in the hayshed and finding the hen-eggs and bombarding the work-horses with them. Jack Fahey also recalls farm holidays spent at Hillside, going around the sheep with his grandfather.

In the 1920's my grandfather, Peter Laurence Mannion and his brother, Joseph William Mannion returned to Clifden and took over the running of the Cradock property, which had been added to over the years through Crown Leases of resumed farming properties. They 'batched' there together, farming and chasing sheep and picking up work around the place. It was through his blade shearing that Peter (P.L.) became friendly with Eileen (Eily) Agnes Williams, one of the thirteen Williams children from Willila, a few miles down the road towards Carrieton. Of the Catholic faith they might have been, but they were also human and the bible tells us 'that we will reap whatever we sow' and the fruits of life dictated their marriage at Carrieton, S.A. in 1925. Joe studied wool-classing and worked at Michell's Wool Processing Works in Adelaide and also spent some time in Tasmania.

Mary Theresa Mannion died at Hillside, on 1 March, 1937 aged 71 and is buried in the nearby Booborowie Cemetery and from her obituary, considered her faith in the Catholic Church very important. Bartholomew, with his son, Patrick and daughters Mary and Nellie, stayed on at Hillside and continued farming until his death from heart failure, at home on 20 February, 1943. He too is buried in the Booborowie Cemetery with his wife. Pat married Mary Murphy from Jamestown and lived in an adjoining 'tin house' at Hillside until the mid 1950s when the property was sold and they retired to Somerton Park in Adelaide.

Bartholomew's brother Joe, in his later years, took up land, a small block also at Willalo, near the Willalo Hall. He sold that and lived a lot of his time with his brother and nieces, Mary and Nellie at Hillside until his death at home on 4 December 1946, aged 84 . He is buried in the Jamestown Cemetery in an unmarked grave; a very undignified end for a pioneering bushman of the state's north during the 1890s ! Bartholomew and his brother, Joe were apparently fairly close, having shared the experience of being 'abandoned' by their parents and travelling to Australia together as youngsters in 1873.

'P.L' and family, and 'J.W.' continued in partnership at Clifden (although my father reckons that it was in name only, as P.L. and Sons did most of the work) and purchased another grazing property, for Joe and his wife, Marie Kavanagh, The Springs, at nearby Bendleby, from Alex Gangel in 1947. The partnership was dissolved in 1951, when 'P.L' took over the running of Clifden in his own rite.

Six children were born to Peter and Eileen, of whom five survived, Maurice Ignatius; my father, Peter Thaddeus William (P.T.W.) Mannion , born at Hawker hospital , 27 miles north of Clifden, on 28 June, 1927; Reginald Joseph; Patricia Mary and Josephine Anne. The Clifden in South Australia differed from its namesake in Ireland in climate and 'life on the land' at Clifden was a struggle at the best of times, especially during the 1930s depression. The boys went to Uroonda School, five and a half miles away, on foot, by horse and on bicycles. The Uroonda School closed in 1947, so the girls started their schooling by correspondence, Pat later boarded at Carrieton with her uncle and aunt, Arthur and 'Doss' Rowe and family and attended the Yanyarrie School, until the shift to Pekina, when she and Jose went to Tarcowie School

According to my father, P.L. Mannion's break came in the mid '30s when "stony broke" he won a road-work contract, stone knapping, for the Carrieton District Council, for £33.00, which entailed breaking several chain of stones, prison-style, with a knapping hammer, down to a useable size for filling on district roads. P.L. also won other contracts digging out the noxious weed, Bathurst Burr along the roadsides, in which he involved the entire family, Mum, Dad and the kids!. P.L. and E.A. had differing political beliefs throughout the years, with P.L. very anti-Labour, but as Eily often pointed out, he wasn't too proud to work for the state when private industry was down and out! P.L.was interested in local and community events and played tennis for Cradock in the 'Far Northern Association'.

The land was not really suitable for cereal cropping, with the rainfall being too erratic, so the Mannion's sowed their last cereal crops at Cradock in 1939 with a yield of 8 bags/acre, and concentrated on sheep grazing and wool-growing, and were very successful in this venture (and still are, with a descendant of 'P.L', my cousin, Kevin Mannion, still running the Clifden property.)

During their time at Clifden, Peter and Eileen never had electricity of any form, no telephone and used kerosene lamps for lighting, a wood stove for cooking and relied on a dam and underground rain-water tank for domestic water and were generally self reliant and self sufficient. Eventually, Arthur Rowe, Eileen's brother in-law from Carrieton gave them a kero fridge. The property was not viable to support a growing family, so Maurice and Pete found work around the district working in shearing sheds and eventually both became good shearers, travelling extensively in the northern areas on their Triumph and Ariel motor-bikes, after the Second World War. A lot of their work was in the Quorn area of the Flinders Ranges and it was in Quorn that my father, Pete met Carmel Finlay, a shop assistant at 'Foster's Emporium' a drapery and haberdashery store. The Finlay family farmed in 'Richman's Valley' south of Quorn and were also keen and successful sporting family, involved in athletics and horse-racing.

Through his successful involvement in the merino sheep industry, P.L. Mannion made many contacts throughout the state and one of these was Mick Caulfield, a farmer from Pekina, a township and district 50 miles south of Cradock in the mid-north. Caulfield apparently told P.L. that his neighbours, Frank and Dora Kenny were selling out and that it wasn't a bad place, so..............

In 1952 P.L. and E.A. Mannion and family, Maurice (25),Pete (P.T.W. 24), Reg, (20), Patricia (12) and Josephine (9), moved back into the 'inside country' at Pekina, a mixed farming district with a 14 inch annual rainfall, about 8 miles south of Orroroo and not far from Coomooroo. P.L. didn't have a truck, so he got Colin Fogden, and his son, Ray, carriers from Carrieton to carry the bulk of their goods and chattels down, while the boys made several trips back and forth with a four wheeled rubber tyred trolley, drawn by two horses. On the initial trip, they tied their saddle horses (hacks) to the side of the trolley and they had no choice but to jog along beside. After the move to Pekina, they retained their Cradock property, Clifden as a grazing proposition and one of the harness horses, Major, found his way back to Clifden and died there a couple of weeks later (homesick!?)

The property they bought at Pekina, was in the Pekina Valley at the western base of the 'Hogshead Hill', and they named it Clifden Vale and it was operated as P.L. Mannion and Sons. Through success at wool growing, with wool prices at a premium, cereal farming and working for wages in the shearing industry, the Mannion's eventually bought three more farming properties in the Pekina district, one for each of the sons. Pete moved into Dempsey's, about a mile east of Pekina, Maurice went over the hill, towards Wepowie, to Kitto's and Reg eventually settled at Redden's about half a mile south of Pekina.

The Pekina district was a close knit Irish/Catholic community and was a bit overwhelmed at these 'northerners' buying up large parcels of 'their land' and whilst being Catholics, the Mannion family have always felt like 'outsiders', despite being involved in church, community and sporting events. Some of the Pekina 'locals' still recall P.L. riding around the district on horse-back after his arrival at Pekina, which they considered unusual! Despite retaining and practising their Catholic faith, Mannion's found some of the Pekina practices a bit restrictive : Eily was not allowed to wash; or at least hang out the clothes, on a Sunday in case a 'would be' prominent local saw it!. The same bloke, a few years later, upon learning that my father was going to kill and dress a sheep on the Sabbath, warned him that it (the carcase) would "go black on the hook", Dad told him that the previous three hadn't! But they must have done something right, as eventually P.L. inherited the job of 'taking up the collection plate' at Sunday Mass and after he died Dad got the job, which he still has.

The relationship between P.T.W. and Carmel Finlay blossomed and eventually they were married at Quorn on 1 May, 1954. Following a honeymoon to Melbourne, they returned to Pekina and settled on the "Dempsey" farm. P.T.W. was in farming partnership with his father and brothers at Pekina and Cradock and while this kept him busy he also continued shearing around the area. Carmel, being a 'newcomer' to the district and being unable to drive a motor-car must have found it a daunting and lonely experience, however, she didn't have a lot of spare time on her hands, trying to establish a run-down old farm house with limited washing facilities and an outside 'long-drop' dunny and with a 'honeymoon-baby' on the way!

Pete and Carmel tried to assimilate into the church and sporting communities, playing cricket and tennis. On 20 March, 1955 at 2a.m. John Francis Mannion was born at the Orroroo Hospital, nine miles from Pekina. The Mannion 'boys' were not really familiar with cereal cropping, but with some neighbourly advice, observation and after many hours on their open 'Massey-Harris' 744D and 'Twin-City' tractors, in the frosty Pekina winters pulling bridle draft cultivators and 'Shearer' combines, followed by many more in the heat and dust of summer, they eventually became adept farmers. But their real passion was sheep and as P.L. and his brother, Joe had both established stud flocks, it must have been inherited, or conditioned, and their shearing ability guaranteed them off-farm incomes, which is what they lived on, as the 'Boss', P.L.wasn't noted for his generosity! In the early 1960's they built a new shearing shed and it was commissioned with a grand opening. The three brothers with P.L. as the boss, operated as an efficient, but not always amicable, team and between them they could just about fix anything, from cars, trucks and stationary engines to windmills and pumps, but it was with sheep that they stood out. I remember, as a boy watching them, Dad, uncle 'Maurie' and uncle 'Regie', castrating ram lambs and pulling the testicles out with their teeth, their faces covered in blood and guts. Shearing was a big occasion too, with all hands 'on the board'. P.L. was also interested in Red-Poll cattle and established a Stud, 'Pekina-Lea', which was disposed of in the early 1970s.

Some of my earliest memories of Pekina are the reflections of the firelight on my bedroom wall, after Dad had lit the wood-stove, first thing in the mornings and I can always remember Dad going away shearing on Sunday afternoons, heading off with an old yellowish, fibre suitcase with a grey army blanket strapped to it with a brown leather strap. Where he was going or how he got there, I have no idea. I also remember vaguely, going to Clifden, sitting on the petrol tank of a motor bike in front of my father. Two other children were born to Pete and Carmel, another son, Gary Vincent Mannion, in 1959 and Anne-Marie Mannion in 1963.

Despite his limited education at Uroonda School (one room-one teacher) my father developed a remarkable mechanical ability and is able to fix most things. He possesses the three 'm's' essential to being a farmer: to mend, make and maintain machinery. This probably evolved through interest and necessity and my brother Gary and I have the same ability and stubbornness to fix things, whether we like it or not.

The family partnership was eventually disolved in 1969, following Maurice and Margaret Mannion's return to Cradock, from Pekina with six children, where they had increased the original holding by buying out the neighbours, Burt's, which they then called Clifden, too. They eventually had eight children and stayed at Cradock until Maurice died on 13 October, 1993, aged 67 at Hawker; his son, Kevin now runs and lives on the place. Reg Mannion stayed in Pekina, but increased his holding, buying land in the Yatina hills, where one of his two sons, Tony now lives. Reg eventually moved to western New South Wales where he lives with his wife, Donna on a sheep grazing property. Pete and Carmel are still at Pekina, farming wheat and barley, and running merino sheep for wool production and fat lambs for meat.

My grandpa Mannion, P.L. died on 5 October, 1974, aged 74 in the Booleroo Centre Hospital and is buried at the foot of Mt. Maurice in the Pekina Cemetery. He was a proud man, proud of his success and achievements in setting up his sons on their own properties and well he should have been, but he was a 'man's man' (but not a boozer) and lived a man's life of 'stockwhip and shears' and didn' t approve of women's involvement in business. Typical of many family farm operations, he did not get on with his sons at times, especially my father, and disapproved of my parents decision to send me away to learn a trade ( a decision I didn't really like at the time either!) and not stay 'on the land'.

In retrospect, I don't think my 'grandma Mannion', Eily ever really liked living at Pekina and always yearned to go back 'up north' to Carrieton and her family. On several occasions she was admitted to the Booleroo Centre Hospital suffering from depression, this wasn't common knowledge, but that was in an era when such things weren't talked about! But she had a kindly disposition and although not 'house-proud', her house always had 'open doors'. I don't think she had an easy life with her husband and due to his frugality she spent a lot of time milking cows and sending the separated cream to the Orroroo Butter Factory to get some regular income. She loved her grandchildren and in my early years I can recall Christmas' at Clifden Vale, with lots of relations and heaps of food around, and a native pine Christmas Tree adorned with silver-frosted pine cones, in the corner of the dining room. I can remember too, her cream and sugar sandwiches and later on the big tomato sandwiches, made with fresh bread; she was a wholesome cook and always had a 'pinny' on.

Following the death of her husband, Eily, or E.A. as she was sometimes known, took on a new lease of life and enjoyed her new found freedom, going on several holidays and 'gallivanting' around the district in her old red Falcon car. Eileen Agnes Mannion died in the Booleroo Centre Hospital on 9 February, 1982, aged 75 and she is also buried in the Pekina Cemetery.

On Thursday, 24 September, 1998, the Mannion family will gather again at the foot of Mt. Maurice to bury my fathers elder sister and my aunty, Patricia Mary Mannion, who died in London, on 12 September, 1998, aged 57. Pat grew up in the Pekina/Tarcowie district after the move from Cradock, but later went to boarding school in Adelaide. She was a bit of a radical for a woman of the 1950's, born into a conservative Irish/ Australian Catholic farming family. she never did marry or have any children, neither did she expect any man to keep her. She did have a relationship with a local bloke, but her mother didn't approve and that was doomed; an event Pat never really got over and she devoted her life to her career, nursing. She drifted around a bit and shifted to Casterton, Vic. where she studied nursing, eventually she went to Western Australia where she continued nursing and through her studies eventually became Deputy Head of Undergraduate Studies - Clinical Liaison, in Nursing at Curtin University, Perth. W.A.

In 1997, Pat was diagnosed as having bowel cancer and despite treatment never recovered and died in London, U.K. while on holidays. Her body will be flown to Adelaide for transport to Pekina to join her parents.

But life must go on! and despite the myth that Australian/Irish Catholic families breed prolifically, the Mannion's haven't really caused a population explosion, only in small bursts! I have only one daughter, Nell Grace Mannion, born 12 May 1990, at The Queen Victoria Hospital, Rose Park, Adelaide, but, that's another story.

My great great grandfather, Patrick Monaghan, was born in Clifden about 1826, the son of John Monaghan and Mary Kennealy. I know nothing of the early life of Patrick or of his parents or if he had any siblings. During the period of 1845 to 1849, the West Coast of Ireland was badly hit by the famine. The Slater's Directory of 1846 lists Patrick's father, John, under Public Housing but he is not listed in the 1855 Griffith Valuation. One can only assume that Patrick's parents died during the famine.

The famine drove people to extreme measures, such as stealing, in order to survive. Patrick was one of these and he was convicted of stealing a pig on 26 June 1848. A copy of trial details lists the surname as Menahon not Monaghan. His punishment was transportation to Australia for 7 years. So, with prison number 49868, he left Ireland aboard The Havering, the second last ship to transport convicts to New South Wales.

Captained by J N Fenwick, the ship departed Dublin on 4 August 1849 with 336 passengers on board and arrived in New South Wales on 8 November 1849 with 334 passengers. There were objections to convict transportation at the time so the prisoners were not allowed to disembark and were sent on to other ports.

The Havering continued up the east coast of Australia to Moreton Bay, off loading convicts to the Hunter River area, Port Macquarie with the final 30 landed at Moreton Bay. On disembarking on the 30th November, all convicts were granted a ticket of leave. On 11 March 1850, Patrick was granted a Ticket of Leave Passport to work out his sentence in the service of Mr Thomas Bell. Mr Bell was a native of Northern Ireland who owned Jimbour a very large sheep station near Dalby in Queensland. Patrick worked as a farm labourer whilst at the station.

Catherine Nelligan was born in Kilfenora in 1839 and came to Australia on The Persia in 1856 to work as a domestic servant at Jimbour Station. It was here that Patrick met Catherine and they married in 1858. They had 7 children, six of whom were born at Jimbour. The first born was Michael in 1859, followed by John in 1861.Their other children were: William (my great grandfather) born on 18 December 1862, Patrick in 1864, Mary in 1866, Lizzie in 1869 and James in 1874. Sadly, the two eldest, Michael and John, died of Croup in mid 1864, 22 days apart and both are buried in the Jimbour Cemetery.

Tragedy struck Patrick again when Catherine died of Puerperal Fever 2 days after giving birth to James in August 1874. More sadness was to come when James died three months later from Dysentery. Patrick raised his remaining children on his own. School records show that both girls attended school at Jimbour but there are no records for the boys attending school.

In 1878, Patrick selected 720 acres of land in the parish of Kamkillenbar, now know as The Bun on the Bunya Highway. Here he raised his own beef which he then slaughtered in his butcher shop at Kamkillenbar.

He obviously prospered in this venture and was able to purchase a large parcel of land in Dalby in May 1880. When Patrick died on 18 October 1902, he had 200 pounds in the bank which at that time was a large sum of money. 150 pounds was to be shared among his four surviving children, William, Patrick, Mary and Elizabeth and any land owned was to be sold with this money also shared among these children. The remaining 50 pounds was used to purchase a headstone for his grave with any leftover being given to the Catholic Church for prayers to be said for his soul. This headstone remains standing in the Dalby Cemetery today.

Patrick's oldest surviving son, William, became the head stockman at Jimbour in the late 1880s and continued to live on the station until early 1900. He then selected his own land and married Jane Mackie, a native of Scotland, who was a domestic servant at Jimbour. They raised a family of 10 children and their eldest son, William, was my grandfather.

Patrick's descendants in Australia number 431 of whom 375 are still living to this day with the oldest being my father, Kevin, who will be 90 in August this year.

Greg Monaghan

Queensland

Australia

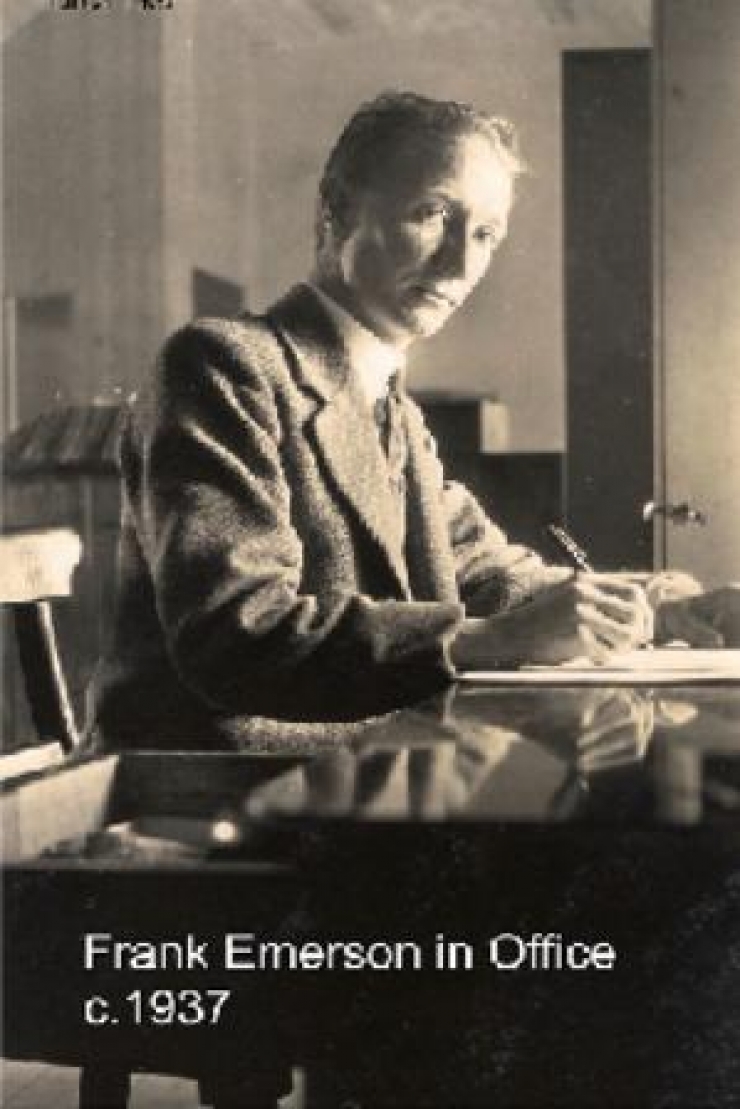

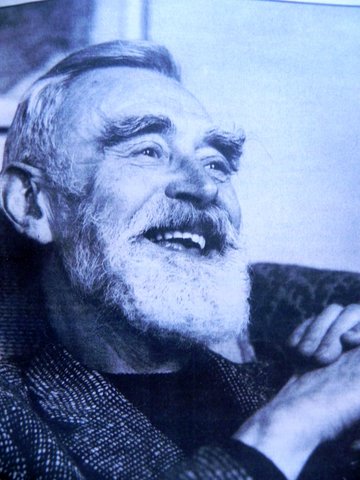

Maurice Gorham 1902 - 1975

Noted broadcaster and author, and member of a Clifden family.

Maurice Gorham was a household name in Ireland in the 1950's ... as Director of Broadcasting in Radio Eireann ... for people who can remember the period of the radio soap entitled "The Kennedy's of Castleross" and programmes such as "The School Around the Corner", "Take the Floor" and Tommy O Brien's operatic recordings. Maurice's father was a native of Clifden who had studied medicine in Queen's College Galway (now NUIG) in the 1870's. his paternal grandfather Anthony Gorham came from north Connemara and became a successful merchant in Clifden .. One of his premises was on the site of what until recently was the AIB bank on Market Square. His tombstone is just inside the entrance to the old cemetery opposite the Catholic church ... the carved inscription still remarkably clear. Anthony Gorham had married twice and his second wife Honoria, was from an old established Clifden family ... the Coneyses, many of whom had been medical doctors. (In many of his published books Maurice Gorham gave his full name : Maurice Anthony Coneys Gorham.) It seems that four of Anthony and Honiara's sons qualified as doctors .. Two, joined the British Royal Navy as medical officers, one, known as Pit remained in Clifden and Maurice's father, practiced in London. There are some old Gorham tombstones in Ardbear cemetery on the outskirts of Clifden, and although the name of John James, whose career was in the Royal Navy, is marked on the headstone, it seems he died and was buried abroad, but at his mother's request his name was given along with other deceased family members in that graveyard. (Information given by the late Desmond Morris, Clifden).

Maurice Gorham was a household name in Ireland in the 1950's ... as Director of Broadcasting in Radio Eireann ... for people who can remember the period of the radio soap entitled "The Kennedy's of Castleross" and programmes such as "The School Around the Corner", "Take the Floor" and Tommy O Brien's operatic recordings. Maurice's father was a native of Clifden who had studied medicine in Queen's College Galway (now NUIG) in the 1870's. his paternal grandfather Anthony Gorham came from north Connemara and became a successful merchant in Clifden .. One of his premises was on the site of what until recently was the AIB bank on Market Square. His tombstone is just inside the entrance to the old cemetery opposite the Catholic church ... the carved inscription still remarkably clear. Anthony Gorham had married twice and his second wife Honoria, was from an old established Clifden family ... the Coneyses, many of whom had been medical doctors. (In many of his published books Maurice Gorham gave his full name : Maurice Anthony Coneys Gorham.) It seems that four of Anthony and Honiara's sons qualified as doctors .. Two, joined the British Royal Navy as medical officers, one, known as Pit remained in Clifden and Maurice's father, practiced in London. There are some old Gorham tombstones in Ardbear cemetery on the outskirts of Clifden, and although the name of John James, whose career was in the Royal Navy, is marked on the headstone, it seems he died and was buried abroad, but at his mother's request his name was given along with other deceased family members in that graveyard. (Information given by the late Desmond Morris, Clifden).

Maurice Gorham spent summer holidays as a child in one of the Gorham family properties, today known as Gleann Aoibheann, Beach Road and now the home of Breandan O Scanaill. He wrote "I had grown up as an Irishman in London. My father had been dispensary doctor at Letterfrack, gone to England, and practiced first in Lancashire and then in London, where I was born". he started school in London and was later sent to a Jesuit public school, Stonyhurst in Lancashire. He studied history in Balliol College, Oxford and one of his contemporaries there was the film actor Raymond Massey. He started a journalistic career with a Westminster paper and then the Radio Times newspaper in London in 1926 and progressed to being its editor for eight years. In 1941 he moved into broadcasting with the BBC.

Gorham lived through wartime in London and he was involved with extending BBC services overseas, being based for a time in Berlin with Allied Expeditionary Forces Programme. There he met up with American broadcasters and learnt a lot from their more developed techniques in outdoor broadcasting. He introduced some new developments in outdoor broadcasting to the BBC and also launched the BBC's second programme which he entitled the Light Programme. Maurice Gorham left an account of this period in a book entitled "Sound and Fury ... Twenty One Years in the BBC". then Maurice Gorham became involved with re-establishing television service in Britain, which had been closed down since September 1939. He remained there until 1947 when he resigned to a number of books and feature programmes for the BBC. He was instrumental in persuading the aged George Bernard Shaw to a noted televised interview.

As he wrote: "the suggestion of the job with Radio Eireann came out of the blue in July 1952, first from F.H. Boland who was the Irish Ambassador in London and then from Erskin Childers himself .... The offer appealed to me enormously, I would not have wanted a regular job anywhere else ... I had always wanted to live and work in Ireland and here at last was my chance. I was in fairly close touch with life in Ireland, I had of course relations still in Connemara (though by now none of my own name). Gorham was a member of the University Club in Dublin while working in London. Gorham started as Director of Broadcasting in Radio Eireann on January 1 1953, and remained there until 1959.

As a gifted writer we are lucky that Gorham was requested to draft an account of the early years of broadcasting in Ireland: "Forty Years of Irish Broadcasting", published in 1967 with a forward from the then Chairman of Radio Eireann, Dr. "Tod" Andrews. It is a witty, readable and accurately researched work covering the main developments in Irish broadcasting history, starting with detailing the conditions in the studios when he started to work in Henry Street, Dublin which he described as "incredibly outdated" the acoustics provided by dusty old Army blankets draped from the ceilings which had been there since 1928. Receptionists would have been considered too expensive so the work was done by a Post Office Attendant ... and there was no library on the premises. "Yet in these haphazard surroundings a number of highly talented people succeeded in doing good work. For general knowledge, intelligence and culture in two languages, the staff of Radio Eireann, could compare with any such organization elsewhere, and some of the programmes, done under enormous difficulties, were first rate".

In spite of the makeshift conditions Radio Eireann, had an extraordinarily talented repertory theatre group, the Radio Eireann Players, and the nation tuned into plays broadcast every Sunday evening: among the noted actors were Seamus Forde, Joe Lynch, Marie Kean, Pegg Monahan, Denis Brennan, Daphne Carroll, Ginette Wadell, Thomas Studley, Eamonn Kelly ... all familiar names to Irish listeners in the 1950's. on two occasions this group of players won the Prix Italia award for Ireland against European competition. Maurice Gorham made every effort to promote serious programming on the national station, launching the Thomas Davis lectures and providing "promenade" concerts by the Radio Eireann Symphony Orchestra and the Radio Eireann Light Orchestra. Previous attempts to create orchestras in Dublin had not survived because of costs. Without funding supplied by the national radio station there would have been no concert orchestras in Ireland ... but some of the Irish politicians objected to expenditure on a minority cultural interest and salaries for mainly foreign musicians! However concerts by the RESO in provincial centres were the first contact many Irish school children had with a real orchestra.

The hours of radio broadcasting were limited in the early 1950's to five and a half hours a day with gaps in programming in the morning and afternoon. The nation was obsessed with religious programming and Radio Eireann chose to transport equipment overland to Italy to relay material on the Holy Year 1950. Gorham detailed all that was expected of the station in spite of its inadequate resources: "It was expected to revive the speaking of Irish; to foster a taste for classical music; to keep people on the farms; to sell good and services of all kinds from sausages to sweep tickets; to provide a living and a career for writers and musicians; to reunite the Irish people at home with those overseas; to end Partition. All this in addition to broadcasting's normal duty to inform, educate and entertain". Commentaries on GAA matches were essential listening and a link-up with Radio Brazzaville in Central Africa transmitted them to Irish missionaries abroad. Philip Greene was the leading sports commentator on "Sports Stadium".

In matters of policy regarding the establishment of a television station in Ireland, Gorham made a significant contribution. Appointed to a Television Committee which submitted reports to the government, Gorham endorsed the concept of public service as opposed to a private, commercial enterprise. For many years the Department of Finance had obstructed requests from the Department of Posts and Telegraph for a television service in Ireland and branded it a "luxury service". At the same time politicians in the Republic of Ireland were embarrassed that television was up and running in Northern Ireland and that the BBC had many viewers in Dublin and along the east coast. National prestige was at stake. Some Irish politicians were attracted by the idea of allowing a purely commercial service (along the lines of "Radio Luxembourg") that would operate independently and not be a burden on Revenue. Naturally the Department of Finance was also keen on the idea of a commercial enterprise. The Television Committee submitted many reports to the Government which generally favoured the public service ethos, and these were always forcefully opposed by the Department of Finance, even as late as 1957.

Leon O Broin, Secretary to the Department of Posts and Telegraph, worked with Gorham on the Television Committee and they considered all the options. Gorham did not favour the American model where newscasts were interrupted by advertising for soda pop or Ford cars. O Broin went to London and discussed ITA's policies with its director Fraser in Britain ... how they imported many US programmes etc. Gorham then stated that if the Irish service had to choose between ITA and BBC, as its main prop, the ITV should be the station selected as it was more popular and had less British propaganda than the BBC! Gael-Linn, which had built up expertise in filming news documentaires distributed in Irish cinemas, was also a contender in the running of the proposed new television service. O Broin and Gorham testified to the Television Commission and eventually it was decided to create an independent authority, free from the Department of Posts and Telegraph, to take over broadcasting and radio in Ireland. Gorham was concerned for the survival of radio, while accepting that the introduction of a national television service was both necessary and desirable.

Leon O Broin referred to Gorham as being indispensable to the planning of an Irish television service because of his understanding of international broadcasting agreements and the technicalities involved.

Having had to endure the turmoil of the conflicting interests of politicians and civil servants in the lead up to the establishment of RTE, Maurice Gorham was probably happy to retire and concentrate on writing. He then found time to set up the Writer's Museum in Dublin which he hoped would be a major cultural centre in a city which had produced so many literary giants from Swift to Joyce, and a couple of Nobel prize winners in literature, W.B. Yeats and G.B. Shaw. There is a Gorham room on the first floor of the Dublin Writer's Museum and some works from his personal library were donated to the Museum by Gorham's sister, after his death.

Gorham campaigned for the preservation of Georgian architecture in Dublin and protested when the ESB removed old Georgian house facades to build its new headquarters. Gorham had been enthralled by the wealth of architectural remains still visible in Dublin which had been spared wartime destruction, compared to London where railings had been removed for the war effort and buildings destroyed in the blitz. He loved the atmosphere in the Dublin pubs and admired the courtesy and professionalism of the local bar workers. He published several collections of old photographs taken in Irish locations, entitled "Ireland Yesterday" (1971), "Dublin from Old Photographs" (1972), and "Ireland from Old Photographs" (1971).

While in London Gorham had enjoyed live performances in circuses and fairgrounds and wrote an interesting book along with illustrator Edward Ardizzone entitled "Showmen and Suckers" (1951) ... giving quite hilarious descriptions of wrestlers and other performers.

Gorham's writing style is not dated and is still eminently enjoyable. According to RTE librarian, Malachy Moran, Gorham's book "Forty Years of Irish Broadcasting" (1967) is considered by the staff as the station's Bible when the history of Radio Eireann had to be consulted and its records checked. Gorham had an amazing range of cultural interests ... music, art, theatre and film, and yet mastered all the technicalities demanded by the new media ... radio and television. Ireland owes Maurice Gorham a great debt for fostering all that was best in its cultural life at a pivotal period in history during his short but remarkable career as director of Broadcasting with Radio Eireann.

Catherine Jennings

(Article based on information given by a cousin of Maurice Gorhams' the late Desmond Morris of Ben View House, Bridge St, Clifden. Books by Gorham are to be found in different libraries: "Sound and Fury" was in TCD. The books reproducing old photographs of Ireland are in the National Library and are sometimes available from second hand book dealers. There is a Gorham archive in RTE. Lectures on Gorham have been given by Brian Lynch, formerly of RTE.)

Quotations in this article are from "Forty Years of Irish Broadcasting".

A general study of broadcasting in Ireland in Gorham's era:

Robert Savage: Irish Television, The Political and Social Origins, Cork University Press 1996.

The Famine years were particularly harsh all over the west of Ireland, and especially in the Connemara region whose population of tenant farmers and labourers depended almost entirely on the lumper potato. Thousands died when the potato crop failed in the summer of 1845 and failed again over the following three years. Those who managed to survive were weakened by years of hunger and disease and found it difficult to restart their lives as their work tools, farm implements and furniture had been sold to raise money for food. This was the environment into which the Irish Church Missions stepped when it began its proselytising work in Clifden in early 1848. Its arrival, with plentiful supplies of food and clothes, must have seemed like a godsend to the starving poor of Connemara.

The Famine years were particularly harsh all over the west of Ireland, and especially in the Connemara region whose population of tenant farmers and labourers depended almost entirely on the lumper potato. Thousands died when the potato crop failed in the summer of 1845 and failed again over the following three years. Those who managed to survive were weakened by years of hunger and disease and found it difficult to restart their lives as their work tools, farm implements and furniture had been sold to raise money for food. This was the environment into which the Irish Church Missions stepped when it began its proselytising work in Clifden in early 1848. Its arrival, with plentiful supplies of food and clothes, must have seemed like a godsend to the starving poor of Connemara.

The Irish Church Missions was established by Revd Alexander Dallas, the Church of England rector of Wonston in Hampshire and had been active at Castlekerke, near Oughterard since 1846. Its ambition was to convert the Roman Catholic population of Ireland to scriptural Protestantism and it was handsomely funded by the Protestant population of Great Britain. The Irish poor who attended the Irish Church Missions schools and churches of received clothes and food in addition to educational and religious services and, with the west of Ireland in the midst of a dreadful famine, it is unsurprising that the poor of Connemara eagerly flocked to the Protestant Irish Church Missions. Within a short time the mission could correct claim a very large number of converts or 'jumpers' as they were known. [It is thought that the term Jumpers comes from the Irish expression d'iompaigh siad – they turned.]

The mission's attraction was undoubtedly its provision of food but it chose to interpret the vast attendances at its schools and services as unquestionable proof that the Irish poor were ripe for conversion and, in January 1848, it extended its operations westwards to cover the whole of Connemara. When the mission undertook work in a locality, it established schools where children were taught during the day and adults at night, and where divine service was held until purpose-built mission churches were built. Schools were clustered into mission districts under the control of a missionary clergyman and scripture readers went out through the countryside, visiting houses, reading scriptures and leaving a parcel of food as they left. Unsurprisingly, the famine-stricken inhabitants of Connemara urged them to return again soon and pleaded an interest in the scriptures.

A very large work-force of teachers, scripture readers and clergymen was maintained by the mission. In 1852, it operated thirty-seven schools in Connemara where it maintained nine clergymen, fifty-seven scripture-readers, fifty-one school-teachers, paid out of donations to the mission, which amounted to £12,688 that year. Its English supporters were assured of its success, convinced by an endless output of reports of huge attendances at its schools and services. At this time, it seemed that a successful nationwide campaign was feasible. Bolstered with the prospect of success, funds flowed into the mission's coffers; by 1854 its annual income had grown to £40,089 and in time, the mission would establish sixty-four mission schools west of the line from Spiddal to Leenane. It also established residential homes for destitute children at Clifden (Glenowen for girls and Ballyconree for boys), at Spiddal (Connemara Orphans Nursery) and later at Leenane (Aasleagh Children's Home).

Clifden became a popular destination for English supporters, eager to view the progress of the missions. Its hotels were filled to overflowing in August 1852 when 127 English visitors arrived to witness the consecration of the first mission church at Moyard Bridge (Ballinakill), many of these were English clergymen, secretaries of branches of the Irish Church Missions which had been established in parishes throughout England. These men were greatly impressed by what they saw, one reported that the area which had been essentially Catholic five years earlier had become 'characteristically convert and Protestant ... with a flock gathered and folded by pastors of the United Church'.

The mission answered the two most pressing needs of the poor of Connemara: food and education. Although a government-funded system of education was in place since 1831, the Roman Catholic archbishop of Tuam, John MacHale, forbade the establishment of state-sponsored schools within his diocese and, as the population of Connemara was too poor to pay for privately funded schools, the majority of Connemara people were deprived of an education. As emigration to America was well established by then, the parents of Connemara were keenly aware of the need to equip their children with the basics of reading and writing and a knowledge of English and eagerly sent their children to mission schools to correct this deficit. Adults, who had been reared without schooling, attended the night schools so that they also might learn to read and write.

Of course, the mission provided more than food and education; it also provided scriptural instruction and instilled a contempt for Roman Catholicism in its pupils. It had, after all, been founded with the expressed purpose of converting the Catholic population of Ireland to scriptural Protestantism or, as contemporary publications explained, it hoped to rescue Irish Catholics from the 'errors of Rome'. While its provision of food and education were laudable, the methods employed to imbue a hatred of Catholicism were less savory. For instance, a daily exercise in its schools was that pupils learned off one of the 'twenty-four Reasons for leaving the Church of Rome'. It was totally insulting in its condemnation of the Roman religion, an attitude it instilled in those who attended its schools and services.

As might be expected, the Roman Catholic Church was far from thrilled at what it considered an aggressive attack on the faith of its flock. It had good reason to be alarmed at the speed and extent of conversions; the Irish Church Mission's 1854 annual report told that only eleven families stayed away from the mission in Errismore (Ballyconneely), a district of four hundred families. Religious toleration and interdenominational respect were severely lacking in the nineteenth-century, either in Ireland or throughout Europe. Protestants were certain that no member of the Church of Rome could possibly enter heaven and Catholics were convinced that they, and only they, would get through the Pearly Gates. For this reason, and for this reason only, a vicious battle was fought for the souls of the poor of Connemara who found themselves as pawns in a power struggle between the churches.

While reports of landslide conversions to Protestantism may have gladdened the hearts of mission-supporters, the Catholic hierarchy was horrified by revelations of this nature and devised plans to halt 'perversions' and to encourage converts to return to their original faith. As the mission's primary method of interacting with the poor was the provision of food and education, the Roman Catholic Church set out to answer these needs. It established societies of the St Vincent de Paul to distribute charity and it opened rival national schools beside mission schools. It organized a series of parish missions beginning in Oughterard in 1852 and in Clifden the following year at which converts were pressurized into returning to the Church of Rome and where landslide reversions to Catholicism ensued. This did not entirely obliterate the mission's successes, however, as a substantial convert community persisted in Connemara and the mission continued to receive a steady trickle of conversions over the following decades, particularly in years of bad harvests.

The Catholic Church maintained an aggressive attitude towards those who associated with the mission and soon learned that, in a rural community, the most effective method of countering the mission's success was to incite the laity against the converts. Methods inside and outside the law were employed, which ranged from total ostracism to physical violence and the mission claimed that attacks on its property, staff and converts increased whenever Archbishop MacHale visited the region. Converts were beaten up and excluded from fishing boats, their property was damaged and they were deprived of employment so that they were forced to weigh the benefits of mission-involvement against the social costs of conversion.

Inter-faith hostility escalated in Connemara, especially in the 1850s; it would recommence in 1879 when violence to converts forced many lukewarm adherents of the mission to completely distance themselves from the Protestant faith. In the early years, the mission commanded the support of many landowners and, with the break-up and sale of the D'Arcy and Martin estates after the famine, many English supporters bought tracts of land in Connemara to assist the mission, while Catholics purchased land to obstruct its operations. For example, Elizabeth Copley purchased land at Patches, near Claddaghduff to further missionary progress while Henry Wilberforce, a convert to Catholicism, acquired land on Inishboffin for the opposite reason. Landlords varied in their attitude to the mission and its convert community. Some evicted those who adopted the Protestant faith. Others granted land on favourable terms to converts so that, over time, converts tended to cluster on lands of mission-supporting landlords as when Sally O'Donnell, a convert-widow evicted in 1853 from the Blake lands at Errismore was granted a holding at Calla by W.B. Smythe, a supporter of the missions. Sally continued to suffer for associating with the missions; in 1855, two attempts were made to set her house on fire with considerable damage done on the second occasion. When Sally's daughter, Anne, a former teacher at Derrygimla school, died of consumption in 1860, a mission reported that Ballyconneely's priests

... cursed them all, and poor Anne after her death .... They quenched the candles at mass, rang the bell and told them she was burning in the fires of hell; and then cursed anyone who would sell to, or buy from the mother, brother, or any of her family, or any of the 'jumpers' who accompanied her.

The mission made great progress in its initial years but, once the extreme years of the famine passed and the Catholic Church provided education and charitable relief, its appeal was diminished. Catholics were ordered not to speak to converts, not to employ them, to bless themselves if they met one on the road, to totally ostracize them in every way. Few managed to withstand this pressure and substantial reversions to the Catholic ensued. People often retained an association with the mission but reverted as death approached and sometimes these reversions were not entirely voluntary. Reports of Clifden Petty Sessions frequently recount death-bed violence between Catholic and Protestant clergy who battled for the souls of the dying and in some instances, lifelong and firm converts were 'reconverted' after death.

The poor of Connemara eagerly flocked to mission-schools until Catholic schools were opened. Mission-pupils during these initial years proved the most determined and steadfast converts. However, the availability of Catholic education diminished the mission's appeal and attendances at its schools declined markedly from 1855. It failed to gain converts in significant numbers from subsequent generations so that the convert population dwindled as the mission-pupils of 1848-55, died off. By the early decades of the twentieth century the mission was on its last legs; when an elderly Errismore convert died in 1916 it was noted that there was barely enough able-bodied men to carry his coffin.

During its early years, while it was enjoying landslide conversions to Protestantism, the mission was hoped that a nationwide campaign might be undertaken and that all of Ireland would be rescued from the 'errors of Rome'. As it came to appreciate the difficulty of achieving permanent conversions in a rural community, it decided concentrate its efforts in towns and cities where converts could hope for a greater degree of anonymity. It concealed the scale of reversions to Catholicism in Connemara from its supporters who received glowing accounts of missionary progress and who were assured that the faith of Connemara's Catholics had been shaken and that a steady stream of 'enquirers' attended the mission. Supporters in England naively believed that Connemara was becoming increasingly Protestant as the decades passed and continued to donate generously to the cause. They were unaware that attendances at mission schools were comprised of the Protestant-born children of coastguards and not drawn from a local community of converts and 'enquiring' Catholics.

Mission work in Connemara effectively ended around 1880 but even after that time a very small number of Catholics converted or sent their children to mission schools until the early years of the twentieth century. The annual reports of the Irish Church Missions maintained the pretence of a Connemara mission well into the twentieth century, although by that time its operations there had almost ceased. With the death of its last Connemara-based scripture reader in 1937, the western operations of the Irish Church Missions officially came to a close.

Connemara should give sincere thanks that the Irish Church Missions chose to undertake work in the area as the arrival of an aggressive mission forced the Catholic Church to introduce schooling and charitable relief into a district whose needs it had previously ignored. The ensuing interdenominational competition resulted in an impressive provision of education and relief as rival Catholic schools and orphanages were established throughout the district. Many parishes in other parts of the Tuam diocese were deprived of national schools until the death of Archbishop John MacHale in 1881. By then a generation of Connemara people had access to education as a direct result of the presence of the Irish Church Missions.

Image Gallery

Who was Elisabeth Evans?

Three O' Sullivan headstones on Inchagoill

Sarah O' Sullivan, nee Joyce

When I was a young boy my father would bring my brothers and I to Inchagoill on Lough Corrib, each year in early August, to attend mass and pray that we would not drown during the following year. This was probably wise as we were wild young lads, living within 100 metres of the lake, with access to boats at a time when lifejackets were unknown. On one of these pilgrimages I noticed three headstones in the graveyard with the name O'Sullivan. One in particular, the middle one, attracted my attention. Sarah O'Sullivan died in 1884, aged 37. I asked my father who she was.

He said she was his grandmother, Sarah Joyce, and she had died giving birth to his father, Bernard, and his twin brother, John. On her death, Sarah's husband, also Bernard, was left with their 9 remaining children; the oldest Michael was 15. Bernard was farming 26 acres, half of which was bog, yet he erected a headstone to commemorate his wife at a time when headstones were rare. She was obviously special and although I was curious, my father could tell me no more about her.

Many years later, when the genealogy bug struck me, I found a marriage registration in Galway for Bernard Sullivan and Sarah Joyce. They married in Kilmilkin church, in the Maam valley, in 1866. Sarah's father was Tobias Joyce of Culliagh, near Leenane. Tobias turned out to be the second son of Big Jack Joyce, "King of the Joyces", and one-time proprietor of what is now the Leenane Hotel. He had often been written about by the travel writers in the 1830s.

Young Tobias (Toby) Joyce was mentioned in Henry Inglis' traveller's tale, written in 1834, as having a liaison with the beautiful Ms. Flynn of the Halfway House, near Maam Cross. But "the Joyces and Flynns not being entirely as one", and Toby ended up marrying Elizabeth (Eliza) Evans in Clifden Church on 8th March 1840. Toby and Eliza were my great great grandparents.

In addition to my great grandmother Sarah, Toby and Eliza had ten other children. Patrick, the eldest, married his cousin Mary Joyce and settled in Leagaun. They had four children before Patrick died at a young age. Mary later married Martin Acton.

Another son, James B., became a butcher and farmer in Clifden. He later gained some notoriety when he bought Clifden Demesne in 1913 and was denounced from the pulpit by Canon McAlpine as a land grabber.

A daughter, Elizabeth, married John Joyce of Ungwee, Moyard, and their daughter Maggie "Ungee" had a shop in Clifden for many years. Maggie "Ungee" and her first cousin Maggie "Dick" (daughter of the aforementioned James B. and married to Dick Joyce) were regular visitors to their O'Sullivan cousins on the Doorus peninsula in Cornamona.

Elizabeth Evans daughter of Thomas Evans of Cleggan?

But now to my original question, who was my great great grandmother, Elizabeth Evans. Who were her father and mother? Had she brothers and sisters? What did her father do for a living? I think I may know some of the answers but I am not sure.

I think Elizabeth was the daughter of a Thomas Evans of Cleggan. Thomas was seneschal (a sort of small claims court judge) for the Manor of Claremount, of the Martins of Ballinahinch. He died in 1840 as there is an article mentioning his replacement in The Connaught Journal. He is buried in Ballinakill graveyard where, according to Ian Cantwells memorials of the dead, there is an inscription which includes his wife Margaret nee Toole. The inscription states that he was from Cashel, Co. Tipperary, where incidentally Humanity Dicks second wife Harriet Evans came from. I have failed to find this memorial when I visited Ballinakill but a number of memorials lying close to the old church are almost impossible to decipher.

Thomas Evans was a man of the sea and attained worldwide notoriety as a result of claiming to have seen a mermaid "basking on the rocks at Derrygimla, in Errisbeg". This was reported in the Galway Advertiser in 1819 and later appeared in newspapers around the world.

Three of Thomas Evans's sons, Thomas, James and Patrick, are named in a lease between Thomas Martin and Thomas Evans, drawn up in 1828 for the demesne and lands at Cleggan. Patrick was present at the banquet for Daniel O'Connell after the repeal meeting in Clifden in 1843, according to the Nation newspaper. He married Deborah Sloper in Clifden Roman Catholic church in 1839. He was relieving officer for Renvyle District during the famine. Nothing is known of the other two.

Thomas Evans had a fourth son, John, who was drowned off Cleggan in 1828, along with his young wife, Ms. O'Donnell from Louisburg. The report in the Newry Telegraph said it was as a result of "the smarting of a plank" on his father's pleasure boat.

150 years later four O'Sullivan brothers capsized a wooden lakeboat while bringing sheep to an island on Lough Corrib. The prayers they had so diligently lodged, each year on Inchagoill, were repaid with dividends. Only one ewe, that caught her horn in a rib of the boat, was lost. Someone was watching over us that day.

There is evidence that another Evans woman, a Mary Evans, was married to Redmond Joyce, a businessman and Poor Law Guardian in Clifden. Mary was probably Elizabeth's sister, but, as yet, there is no evidence to prove this. Redmond and Mary's daughter, Jane, married John O'Sullivan of Cornamona, a brother of my great grandfather Bernard.

I have set out below details of the Joyce and Evans families. I am just missing some little links, but I am hopeful that someone reading this article might provide a little snippet of information that could crack the case.

By Barry O'Sullivan This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

Elizabeth Evans

Birth About 1820 Cleggan, Co.Galway.

Death 1874 Ashmount, Leenane, Co. Galway.

Father

Thomas Evans (1750-1840) Born Cashel, Co.Tipperary. Buried Ballinakill Cemetery.

Mother

Margaret Toole (1799-1839)

Spouse

Theobald Tobias "Toby" Joyce (1816-1894) son of Big Jack Joyce, Leenane, Co.Galway.

Married 1840 Clifden.

Children