Article Supplied

Website URL: E-mail: This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

Teaching was disorganized from 1700 – 1800 due to the Penal Laws. But Hedge Schools were in existence in this area. The Public Records from the archives in the Four Courts state—

- 1) School in Clifden kept by Michael O’Brien average 50-60

- 2) School in Clifden kept by John Cunningham average 40-50

- 3) School in Clifden kept by Thomas Costello average 30

- 4)

In 1855 the Sisters started a school in a room in the convent. Only one child came to school the first day. Two children arrived the second day. When the numbers increased they got a bigger room in the present laundry. Soon they had 120 pupils. From a humble beginning the school grew, so a new school building was imperative.

In 1855 the Sisters were fortunate in that their first postulant had a knowledge of architecture. She was Sr. Zavier Reville, daughter of Mr. Joseph Reville, Clonmel, and later of Carton, Co. Galway, an ideal directress of the building. Her inspiration added elegance to it. It was skilfully erected with the most enduring material which as we can see has lasted over 130 years. It is impossible to estimate the colossal work that was undertaken and achieved. It must have been a “God Send” for the labourers whom we are told received 6d a day. The Sisters were seriously handicapped for some years by straitened circumstances until the school was placed under the Department of Education.

NATIONAL SCHOOLS 1831

In 1831 the Government awarded grants to a new National Board of Education on which both Catholics and Protestants would be represented. Thus ended the Kildare St. Society. The new National Schools were intended to provide “United Education”. Religious instruction was to be given separately.

Most of the Catholic bishops accepted the new arrangements. But Bishop John MacHale opposed it, demanding Catholic schools for Catholic children.

Hence, it was not until after the death of then Archbishop of Tuam MacHale in 1881 that the new Archbishop, Dr. McEvily directed the Sisters to apply for state aid in order to secure the best possible education and to have success tested by examinations.

Before aid can be granted to a school the school must be in actual operation under competent teacher and the commissioners must be satisfied that the case is deserving of assistance, and has a good average attendance. Before the commissioners apply for aid they require a report from the district inspector.

So on November 25, 1881, Sr. Vincent Ryan applied for State aid. On January 7th, 1882, an inspector Mr. Downing visited the school and stayed from 10:20 a.m. to 12:50 p.m. His report found in the archives in the Four Courts in Dublin, is as follows:

The school is well built, spacious, warm, lighted and well ventilated.

School hours are 10:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m.

Population of Clifden is 1,313.

The school was erected from private funds.

The school is the property of the Nuns.

I can certify that the Nuns are competent.

The local funds supplied annually are Donation: £20.00, School Fees £5.00

The school fees are 1d per week.

About 5/6 pay no fees. They are admitted free by the Nuns, because they say they are unable to pay.

The school is open to all denominations.

Number on roll: Male 37 and Female 148. Total=185, no increase is expected.

The proposed manager is the superiorness.

I recommend that State Aid should be granted.

Signed: E. Downing

A capitation grant was given from January 1882, and alas £5.00 for books.

When Mr. Downing returned in 1884 he wrote – “In the case of Clifden recently placed under, the National School Board I am informed by the clergy and the local people that the connections has (sic) materially added to their former well merited popularity. The four teachers deserve very great praise for thorough fidelity and great zeal.” The number on roll had increased from 185 to 276.

CLIFDEN

When Thackeray visited Clifden in the 1840s, he was so overcome by its beauty that he wrote “the bays of the ocean, the boggy hilly district in which this town lies, opens up its 30 miles of length to the wildest scenery to be found along the West Coast. All one can do is cry ‘BEAUTIFUL!, BEAUTIFUL!’ ”

The scene was soon to change, Black ’47 arrived. The potato crop failed. Many people perished of hunger, or of typhus fever caused by hunger. Historian Sheila Kennedy wrote, “it was amid such scenes that the proselytising societies appeared on the scene with Indian meal for their bait. The Society of Irish Church Missions caught thousands of adults and children in their network of Bible Schools spread over the famine stricken land, and induced to them to renounce the Faith of their Fathers.

Such was the scene when Dean McManus came to Clifden in 1853. He believed that the heritage of the faith was at stake. There were 14 Irish Church Mission Schools in the Parish, e.g. Clifden Boys’, Clifden Girls’, Streamstown, Kingstown, Beleek, Deerylea, Emlough, Rossadillisk, Ballinaboy, Turbot, Duholla, Bunownbeg and Derrygimla.

The Nuns Arrival 1885

Seven years after the Famine the Nuns came to Clifden at the request of the Parish Priest, Dean McManus. He had collected funds in the USA. He bought an acre of land and had a convent built at a cost of £2,700. The Foundation was laid on July 16th 1854 and the building was inhabited 12 months later on 16 July 1855.

The Dean visited the Mercy Convent in Galway which was founded just 12 years previously, and asked for Sisters. They accepted the offer. Five Sisters, the Foundress Mother Teresa White, Sr. Joseph McDonagh, Sr. Vincent Irwin, Sr. Alogsius Dorcey and Sr. Teresa Blake came. They got a great reception in Clifden. The Convent, though complete was damp and unfurnished. The Sisters soon made a foothold in the local community. The first two Sisters named above remained, and the other three returned to Galway.

In 1861 the Newspaper Dublin Builder stated, “they built a Convent and St. Joseph’s Female Orphanage. Fifteen Nuns live there. Most Rev. John McHale and Mr. Thomas Eyre respectively contributed £1,400 and £800.”

In 1881 the names of the four nearest schools to the Convent were:

|

School |

Distance |

Roll |

Manager |

|

Clifden Male |

1/8 mile |

36 |

Rev. P. Greally |

|

Streamstown |

2 miles |

32 |

Rev. B. McDermott |

|

Goulane |

3 miles |

31 |

Rev. B. McDermott |

|

Orphanage |

-- |

38 |

Sr. V. Ryan |

These schools have now amalgamated with the Convent.

1958 – Goulane National School closed and two pupils, Bridie Walsh and Gertie Savage came to Clifden.

1966 – Streamstown National School closed and the pupils and teachers joined us in Clifden

1969— St. Joseph’s Orphanage pupils joined the National School together with their three teachers.

1991 – The Clifden Boys’ National School was amalgamated with the Clifden Girls’ School.

Schools History

(Excerpt from the Connemara News July 1992)

Are presently going through an era of blunders (1991/92)? Should we have allowed this majestic monument to pupils past and present be demolished? Have we made yet another blunder by failing to purchase Woods Field and developing it as a sports centre for the Community?

In this issue we go back in time to the early days of the Secondary School.

In the 1930s Clifden was without any form of Secondary Education. The majority of boys and girls completed their formal education the day they did the Primary Certificate, under the watchful eyes of Rev. Br. Angelo, OSF, and Sr. M. de Sales. For some years the Sisters of Mercy had been contemplating a Secondary School for the girls. Such a venture was not as simple as it appeared. The Sisters of the thirties were living in an era of traditionalism that did not encourage the attendance of Nuns at University or their seeking any distinction in the academic world. UCD, UCG, Maynooth, Sion Hill and Dundalk were yet unheard of in Convent circles, so Superiors sent the sisters to qualify as primary teachers in Caryafort Training College or as nurses in the Mercy Hospital, Cork. As a result, there were few sisters qualified to teach in Secondary Schools.

However, the sisters were well aware of the fact, that from their Profession Day their vocation was to educate. There was no more conscious of that commitment than the late Sr. M. de Sales. Realising that the children of Clifden were educationally deprived, she firmly resolved to seek permission from the Dept. of Education to open what was then known as a Secondary Top for girls. A Secondary Top meant a room or rooms attached to the National School and subject to the National School Branch of Education, and having on its curriculum all subjects required to pass the Intermediate and Leaving Certificates. Permission was finally granted and I assure you it was an oasis in the desert to the parents and girls in Clifden in 1940. (It was not until the end of the decade that the Boys Secondary School was opened by the Franciscan Brothers, where the Clifden Pottery now operates).

The first years of the Secondary Top were difficult years, but true to their traditions, the Sisters worked very hard under desperate conditions. They were fortunate in having on their staff a very dedicated secular teacher, Miss Abina Hickey, B.A., H.Dip., from Bandion who was a fluent French speaker. All subjects on the curriculum were taught through the medium of Irish. It would be difficult for a modern post-primary teacher, in this age of specialisation, to realise that the teachers taught every subject from First Year to Inter class and “still we gazed and still the wonder grew, that one small head could carry all she knew.”

The first Intermediate examination was held in 1943. The result was a 100% success. The first Leaving Certificate was in 1945. Only three pupils sat for the examination that year: May Gorham, Mannin; May O’Toole, Market Street; and Mary Madden, Ballinaboy. All obtained from five to six honours. This was but the beginning of the thirty years of brilliant results from the Convent Secondary School. The names of other girls of the 1940s are Teresa, Frances and Gertie McGrath; Mary Lysaght, Maureen Casey, Phil and Patsy Stankard, Mary McCarthy, Buddy Kelly, Maureen O’Toole, Mary Cloonan, Cissy Coyne, Eileen Malone, Mary Polly, Joy Foyle, Margaret Casey, May Hynes, Eileen Coyne, Breege O’Neill, Agnes Gorham, Breege Gibbons, Rita Burke, Teresa Coyne, Mary and Nora Fitzpatrick, Joan King, Nan Manning, Barbara McCarthy, Gertie King, Una Walsh. These are but a few.

The teachers were Srs. M. Perpetuo, Philomena, Consilio, Miss A. Hickey, Miss A. Ryan.

The Secondary top ceased to exist in 1959. That year it became a recognised Secondary School under the type of liberal education that was so often lauded by the late Cardinal Newman.

Thanks to Sr. Bernadette and Miss Rose Carroll from Kilitmagh, Music had a special place on the curriculum. In the school we had an orchestra, a percussion band, a mouth organ band, a flagellate band, three part choirs and to add to this we did an Operetta and Variety Concert every year. It was the biggest annual event in the locality. Parents flocked to the Town Hall to see their darling daughters perform as cowboys, black and white minstrels, gypsies, French dancers, etc. All the costumes for the various acts were made by the girls themselves under the careful supervision of Srs. M. Jarlalth and Margaret Mary. What nostalgic memories those concerts recall. The musical tuition did not fall on barren soil. One can meet so many past pupils promoting music. To mention but a few—Sr. M. Emmanuel, (Maureen Casey) trained the Garda recruits choir at the Training Centre in Templemore. This choir sang at the church there and at each passing out parade, they performed with the Garda band. Mrs. Tony Mannion, (Buddy Kelly) was an organist and choir trainer in one of the Dublin churches. Mrs. Bertie King (Maureen O’Toole), shared her musical talents with her family, One can only compare the Kings with the Von Trappe family. Maureen played the piano, her husband Bertie, who appeared with Peggy Dell “Peg of my Heart” series on RTE, played double bass. Her daughter Mairead played the piano, cello, violin and guitar. Her son Niall, played the piano and violin. Casting humanity aside, I venture to add to that list the Collooney School Band. The All Ireland Trophies obtained by them in the 1960s date their origin to the training I got in Clifden’s Secondary Top.

1976 saw the opening of the new co-educational Community School at Ardbear, where the nuns, brothers and lay teacher and the boys and girls of the area were all accommodated under one roof. This sadly marked the closure of our Alma Mater and in the words of Paddy Crosby, may “we the pupils of the past, wish every success and happiness to the pupils of the future,” and to the teachers we “Faoi chomairce DE agus brat Mhuire to raibh bhur saothar ar son oglai Chonamara”.

--written by Sr. Phyl Clancy, Mercy Convent, Ballymote, Co. Sligo.

Scoil Mhuire – Clifden – 1991

“It’s like a dream come true”, “history was made today”, “beautiful, beautiful”, “only the best is good enough for Clifden”, were some of the comments made on last Monday, December 9th when the pupils and their teachers changed into the new school. How did the new Scoil Mhuire come about? The merging of the Boys’ School with the Convent School was proposed in 1975 by the Board of Management. A letter from the Department of Education in 1977 read: “Having examined all aspects of the case, it would be in the best interests of all the pupils concerned if the schools amalgamated, thereby creating one central school which would cater for the needs of the children in the Clifden area.”

During the fourteen intervening years there have been meetings, negotiations, deputations and fund raising efforts. Plans were received, examined and changed. But wisdom prevailed, and it was well worthwhile waiting for this beautiful, new, modern school. Scoil Mhuire has eight classrooms, an all-purpose room, a Principal’s room, a remedial room, a kitchenette and a special store room for musical instruments. The work was carried out expeditiously by contractors Jackie and Joe O’Dowd who paid every attention to detail. On December 9th, the first day in the new school, a Mass of Thanksgiving was celebrated at noon by the Very Reverend Canon Heraty P.P., Rev. Previte and Father Hughie Loftus C.C. were also present. During the Mass, Canon Heraty blessed the school. Praying that all those entrusted with the education of youth may teach their pupils how to join the discoveries of human nature with the truth of the Gospel. Mr. Previte spoke of the special love of Jesus for the children. He praised the beautiful school choir for their singing and instrumental music. Gifts at the Offertory Procession were carried by the Management Board. They included a lighted candle, special clay for moulding, rosebuds, bread and wine, and a school register of pupils who had been enriched by their time spent at school over the last hundred years.

So here’s to the next hundred years of education in Clifden. We hope that they will be as rewarding as the last hundred. Here, in this new school a new generation will prepare for life in a new world that few of us can imagine. We hope that they will bring with them an appreciation of the past, and a determination to exercise their imitative, creativity and imagination and use their talent to the full.

They are commencing with a new principal, Sr. Mary Concannon, a new Chairperson, the Very Reverend Canon Heraty P.P. and a new Board of Management. We wish the staff, pupils, parents and management of the new Scoil Mhuire every success. Go raibh bhur saothar faoi chomirce De agus faoi bhrat na Maighdine i gconai.

Clifden New Central School 1991

The merging of the Boys’ School with the Convent was proposed in 1977 by a member of the Board of Management. A letter from the Department of Education in 1977 reads: “I am to refer to previous correspondence regarding the proposed amalgamation. Having examined all aspects of the case it would be in the best interests of all the pupils concerned if they amalgamated, thereby creating one central school which would cater for the needs of the children of the Clifden area.

So now 14 years afterward, Clifden can boast of a beautiful modern 8 teacher school.

So here’s to the next hundred years of education in Clifden. We hope they will be as rewarding as the last hundred. Here a new generation will prepare for life in a new world that few of us can imagine. I hope they will bring with them an appreciation of the past and a determination to exercise initiative, creativity and imagination and use their talents to the full. They are commencing with a new principal, Sr. Mary Concannon and a new chairperson, Canon Heraty and a new Board of Management.

We wish the Staff, Management, Parents and Pupils of the new Scoil Mhuire every success. Go raibh bhur saothar faoi chomirce De agus faoi bhrat na Maighdine i gconai.

Secondary Top 1940- 1959

In the 1930s Clifden was without any form of Secondary Education. The majority of the boys and girls completed their formal education the day they did their Primary Certificate. Some girls went to Kylemore and Taylor’s Hill, and boys went to St. Mary’s or Garbally. The nuns, realising that the children of Clifden were educationally deprived, resolved to seek permission from the Department of Education to start a Secondary Top. This decision had the blessing of the Parish Priest Canon Cunningham who often spoke of the benefits that Secondary Education would bring to the youth of Clifden.

The first Intermediate Examination was held in 1943. Only three sat for the Leaving Certification in 1945: Mary Madden of Ballinaboy, Mary O’Toole of Market Street, Mary Gorham of Mannin.

In 1959 the Secondary Top ceased to exist. It became a recognised Secondary school. Numbers increased. The school had space problems, but prefabs were added.

1976 saw the New Community School at Ardbear – Boys and Girls under one roof.

Page 7:

Clifden Boys School was built about 1866. It had one apartment. It had 111 on the roll. The school was sanctioned in 1882: 120 pupils on the roll: Grant £262.38. –-Manager Dean McManus

The Franciscan Brothers came to Clifden in 1836 at the request of Fr. Fitzmaurice P.P. They built the Quay House and lived there for a few years. In 1853 they bought land in Ardbear and built a school house and monastery there. When Mr. Vesey retired from Boys’ School in the town, Br. Zavier Costelloe became principal there in 1921. Athletics, a school band and gardening were extra curricular activities in the Boys’ School.

Comments from Past Pupils

A newspaper cutting in 1930 from Celia Miller, a past pupil wrote – “The school gave us a wonderful liberal and practical education. Music had a special place on the curriculum – we had piano lessons, and orchestra, percussion band, mouth-organ band, choirs and an annual variety concert or operetta which was the biggest event in the school year.”

Address of Appreciation for the Mercy Sisters of Clifden, April 11th, 2001

Let me begin by saying what an honour it is as a past pupil to be invited to say a few words in recognition of the contribution of the Mercy Sisters to this community, and to remind ourselves of the momentous historical transition that marks their retirement. It is extraordinary to consider what the character of this society was like when the convent was founded in 1854. Decimated by successive years of famine, evictions and land clearances the native population was virtually helpless with no prospect of involvement besides emigration and no institutional structure to provide the skill necessary to compete in the modern world. When Sr. Teresa White visited in 1854 she represented the cutting edge of a phenomenal new movement which would enable young Irish women to play a leading role in the manner in which Irish people generally would respond to the challenges of modernisation. Founded by Catherine McAuley in 1829, it was the most dynamic of all the new religious orders of women associated with the ascendency of Catholic Ireland in the 19th century. It was founded by women for women, and it was almost an exact replica of the Victorian ideal of women dedicating themselves to ‘useful’ work – in this case the training of young women to educate and nurse the poor. In this respect it set itself apart from the more upper-class orders of French origin like the Sacred Heart and Ursuline, and the extraordinary spread of its sister houses across Ireland in the 1830s and 1840s was a testimony to its popularity. The women who led the movement were almost always well to do and highly motivated, wonderful organisers and courageous pioneers who were always on the road sowing the seeds for new convents not only in Ireland but United States and Canada. Such a personality was Sr. Teresa White, who had already founded the Mercy Convent in Galway before she came to Clifden and whom Catherine McAuley considered the most obvious successor to take her place as head of the order when she succumbed to an early death in 1841. Of Teresa White she wrote, of all she is the nearest to me in spirit.

The Clifden convent, which consisted of a primary school and orphanage, was opened in 1855. From then until the mid-70s it functioned as the hub of a revolution in education and modernisation in this area...later adding a secondary school, a technical school for the teaching of domestic science and farm management skills and in the 1960s a boarding school. Its presence meant that any girl within access of the school could avail of the kind of educational preparation that would enable her to aspire to a livelihood beyond the usual trap of domestic servitude that was the lot of the Irish poor. Generations of young women were thus enabled to become civil servants, bank clerks, administrators, teachers, nurses and nuns. In a community where the vast majority of people had to emigrate to make a living the effects of this can hardly be overestimated. The upward mobility allowed by education and career opportunities had a ripple effect whereby women helped their families and raised the standards for what might be expected of their own children. My own earliest memories of the Mercy convent include the dozens of bicycles lined up against the outer wall...a testimony to the number of pupils who cycled to school, some from as far away as Ballyconneely and Moyard in the days before the boarding school was opened in 1965. During the heyday of the boarding school in the years before the O’Malley reforms allowed for free school transport there was a virtual flood of pupils from the more distant areas of Roundstone, Recess and Cleggan.

We would do well to remember the conditions in which teachers had to work in order to accommodate these numbers; in my second and third year in secondary school, for example, I remember that these classes sat together making for a class of between sixty and seventy pupils. Three teaching sisters and one or two lay teachers were obliged to cater to a class of this size, as well as lower and upper classes, and to teach them the full roster of six or seven subjects to prepare them for exams. It has never ceased to amaze me how they could maintain this dedication year after year without a break, without faltering in their standards or otherwise letting down the students. In the days before secretaries and school administrators and career guidance teachers they managed to take care of applications for placement on jobs once we graduated, or paperwork connected with advancing to further studies.

I wish, in connection with this particular point, to remember in particular the legacy of Sr. Immaculae who never failed to put us in for the civil service exams, teacher training applications, etc. In my own particular case when she saw by leaving certificate results that I would be eligible for a county council scholarship to attend university she had the papers sent back to the house of my father to sign because I was out of the country and the deadline was the end of August. That is the kind of example one does not forget. I’m sure it could be documented many times over in the lives and careers of girls who passed through the school and a further point should be made in connection with this example. In a society where resources were limited and opportunities few, the prospect of young women being trained for a career meant surely that they would work at it, there was little point working so hard to become a teacher or a nurse if you were not going to make a career of it. There is a further point to be made here....when remembered what provided the building blocks for the human capital that went into the making of the celebrated Celtic Tiger...surely the values of hard work, accountability and rigorous scholarly discipline instilled by the religious orders should be taken into account when it is remembered that the driving force behind the current boom in our current economic and cultural life was the generation of children of the small farms of the West of Ireland and the working classes of the towns who flocked into the universities and regional technical colleges in the 1970s to become doctors, lawyers and scientists (and the odd academic) – and by whom were we prepared if not by teachers like Sr. Immaculae who worked in anonymity and seldom if ever took public credit for what they accomplished. So it is fitting that we as a community school should recognise the contribution of the Mercy Sisters in the 167 years they have been here; it is a fundamental part of our history and deserves to be recognised as such. The remaining sisters who are with us tonight should be aware of our appreciation as we wish them peace, harmony and rest as they close the doors for the last time and pass the torch to another generation.

Written by Irene Whelan, Sky Road, Clifden – Irene is an Associate Professor of History and Director of Irish Studies at Manhattanville College, New York.

The following is an excerpt from the Illustrated London News, which was the world’s first fully illustrated newspaper, founded in 1842. In the issue of January 5th 1850, the following piece ‘Condition of Ireland, Illustrations of the New Poor Law’ was printed, detailing the journey of the writer through the famine ravaged counties of Clare and Galway.

“I crossed the Bay to Galway, and proceeded towards Clifden by a route devoid of interest, exhibiting, in a less degree than in Clare, the usual signs of devastation in progress. Mr. Martin’s property extends almost the whole way from Ouchterade [Oughterard] to Clifden, and is a mixture of mountain, moor, and fertile land, capable of indefinite improvement, with great facility of water carriage, but most sadly neglected. It is a bad sign for the next harvest, and for the people of this country, that in my whole journey from Galway I did not see more than from thirty to forty persons, including all ages and sexes; and, with the exception of ten men working under a road contractor, few or none of them were at work.

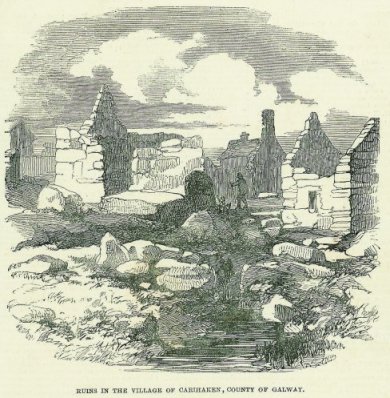

At Carihaken, the levellers have been at work, and tumbled down eighteen houses. In one of them dwelt John Killian, who stood by me while I made the accompanying Sketch of the remains of his dwelling. He told me that he and his father’s before him had owned this now ruined cabin for ages, and that he had paid £4 a year for four acres of ground. He owed no rent: before it was due, the landlord’s drivers cut down his crops, carried them off, gave him no account of the proceeds, and then tumbled his house. The hut made against the end wall of a former habitation was not likely to remain, as a decree had gone forth entirely to clear the place. The old man also told me that his son having cut down, on the spot that was once his own garden, a few sticks to make him a shelter, was taken up, prosecuted, and sentenced to two months’ confinement, for destroying trees and making waste of the property.

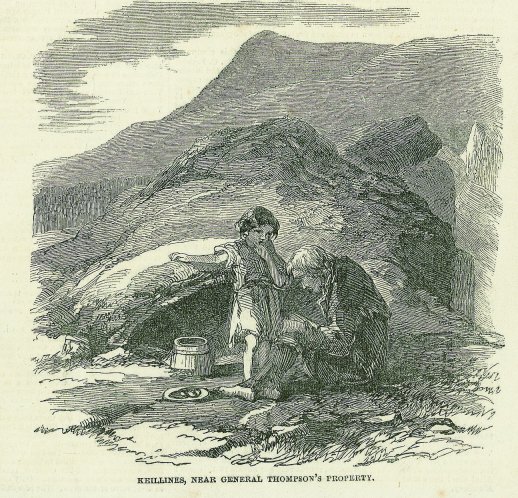

I must supply you with another Sketch of a similar subject on the road between Maam and Clifden, in Joyce’s County, once famous for the Patagonian stature of the inhabitants, who are now starved down to ordinary dimensions. High up on the mountain, but on the road-side, stands the scalpeen of Keillines. It is near General Thompson’s property. Conceive five human beings living in such a hole: the father was out, at work; the mother was getting fuel on the hills, and the children left in the hut could only say they were hungry. Their appearance confirmed their words - want was deeply engraved in their faces, and their lank bodies were almost unprotected by clothing.

At Kylemore my companion bought a turbot, weighing from 18lb. to 20lb., for 1s. 6d., and might have had it for 1s. had he driven a hard bargain. The fact indicates that the sea would supply plenty of food if man would take the trouble to procure it. A similar proof of the equal capacity of the soil is found at a short distance from Kylemore. Two enterprising Englishmen, of the name of Eastwood, planted themselves there about four years ago, and all around them the bleak and barren moor has been changed into well laid-out fields - some green with herbage, and others brown and dingy with the stubble of the carried corn. There is a comfortable lodge, in the Elizabethan style, and around it suitable farm buildings. The whole indicates skill, industry, and good taste; it indicates, too, great courage in overcoming a moral as well as a physical opposition. The Messrs. Eastwood have, in some measure, conquered the habits of the people, which was a more difficult task than subduing the neglected and deserted heath. They will be pioneers to others, who will select, let us hope, this fertile and promising wilderness for the scene of their exertions, instead of wrestling against the arid sands of Australasia, or engaging in competition for the plains of the Mississippi with emigrants from all the countries of Europe. Their example has in fact been followed; and between their abode and Clifden two or three beginnings have been made - so that the country adjoining that town exhibits several signs of improvement.

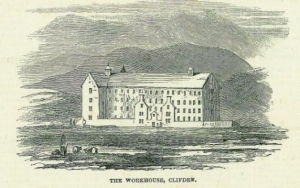

This neighbourhood, before the potato rot came, was not so entirely occupied by the cultivation of the root as some other parts of the country. In the Union of Kilrush, for example, in 1848, there were 11,569 acres under potatoes, out of an area of 178,935 acres; in the Union of Clifden there were only 3714 acres, out of an area of 189,504 acres, under potatoes. The fact is of some importance, in explaining the comparative ease with which the poor in Clifden have been disposed of. Clifden itself is an exotic in an unfavourable climate. It was reared by the patronage of the late Viscount; and since that ceased, it began to decline: the Poor-law has almost finished it. Before we reached, we learned that the guardians of the union were out of money, and obliged to pay for what they wanted by cheques, which they are to receive in payment of the rates. Extreme poverty exists in the neighbourhood - the soil around is poor - great numbers of houses have been levelled - but the poor, unlike those of Kilrush, have in great part disappeared with the houses. They have not found refuge in the workhouse - they have not been carried away as emigrants; they have either wandered away or have died, or both may have contributed to cause their disappearance. I have a list of 111 houses levelled within a few months in the immediate neighbourhood of Clifden, which is very considerable, considering that the whole population of the Union was only 33,465 in 1841. Assuming five inmates to a house, the sixtieth part of the population has been dispossessed. Here, too, there is little more than one person to every six acres; or, scanty as is the population of Clare, the population of the Union of Clifden is not, in relation to acres, half so abundant. I have taken a Sketch of the workhouse, which I send as a memorial of this pet place of the late Viscount Clifden.

[Correction printed in the article of Jan. 19, 1850]

P.S. - I must correct a mistake committed in my last communication. There are two Clifdens in Ireland, and the one in Galway was the property of the D’Arcy family, and not of the Clifden family, as I stated. I am also informed that the Messrs. Eastwood are not English, but Irish-English.

From Clifden to Ouchterade [Oughterard], twenty-one miles, is a dreary drive over a moor, unrelieved except by a glimpse of Mr. Martin’s house at Ballynahinch, and of the residence of Dean Mahon. Destitute as this tract is of inhabitants, about Ouchterade some thirty houses have been recently demolished. A gentleman who witnessed the scene told me nothing could exceed the heartlessness of the levellers, if it were not the patient submission of the sufferers. They wept, indeed; and the children screamed with agony at seeing their homes destroyed and their parents in tears; but the latter allowed themselves unresistingly to be deprived of what is to most people the dearest thing on earth next to their lives - their only home.

I returned to Galway, where the Poor-law officials are not communicative, nor is there in the Union any extraordinary fact to communicate. The old town is a jumble of thatched mud cabins, stone-built houses, and the remains of a former splendour, old sculptures and carvings, putting to shame the homely and even rude houses of a modern date. The people are remarkable for the vivid colours of their dresses, amongst which red predominates, and some lingering traces of a foreign origin may yet be discovered in their countenances. Here, as in most other sea-ports and fishing towns, particularly of Ireland, hulking men lounging about were numerous, and appeared to have every other capacity to work but the will. You are not annoyed, however, by mendicants in Galway, as in other Irish towns, though there is a universal complaint of distress finished by the exclamation, “That last five-shilling rate is a death-blow to all”.

From Galway I proceeded to Ennis, and in the neighbourhood inspected the village of Clear [Clare, later Clarecastle], which had been destroyed within a few weeks, and some part of it within a few days. The Sketch of Pat Macnamara’s Cabin shows the condition of the village. In Ennis I went through the lanes and alleys, and amongst the most distressed part of the population. In one small room, not 20 feet square, I found congregated fifteen people, young and old, exhibiting nearly all the phases of want and squalor. From the smoke which filled the place, it was a Rembrandt scene, and it was with difficulty I could make out the forms of the wretched groups, or of the squalid and dying child on the floor. In the union workhouse of Ennis there is order, decency, and regularity. With it is conjoined a farm of eighteen acres, which is well cultivated by the labour of the paupers. It is wisely placed under the superintendence of one of Lord Clarendon’s practical agricultural instructors; and probably he is as well employed in displaying his skill at the farm as in any other mode of teaching his art.

At Ennis, I consider my tour terminated; and I shall only send you further some general observations on the Poor-law, and some suggestions as to what might reasonably be done for Ireland.”

The full Illustrated London News article can be seen at http://www.clarelibrary.ie/eolas/coclare/history/condition_of_ireland/condition_of_ireland_iln_jan5_1850.htm

Article reproduced here courtesy of Clare County Library.

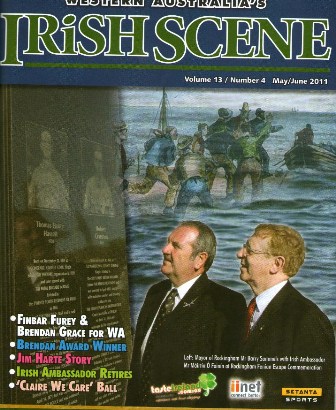

‘Celebrating 200 years of the Wild West’

An article on Clifden 2012 in Western Australia’s Irish Scene Magazine May/June 2011

Almost two hundred years ago Galway native John D’Arcy moved his wife and three children to a remote and isolated landscape that would later inspire writers, poets and painters.

“It was like a wild west town in America,” said local historian and author Kathleen Villiers-Tuthill.

Yielding local resources such as granite, wool and fish, this wild west is not within a cowboy’s holler of America’s wild west. This is the wild west of Ireland.

The area appealed to the twenty six year old D’Arcy who owned over 17,000 acres on the west coast of Connemara. The D’Arcy family was one of the famed 14 tribes of Galway. Their connections and affinity with the west of Ireland were strong and ancient.

John D’Arcy moved to his frontier settlement in 1812 and called the town An Clochan, meaning rocks or stones. In English he invented a new word for his frontier town, Clifden, no one knows why.

“It was a very remote, isolated area and there were very poor quality roads and in some cases no roads at all connecting it with the nearest towns which would have been Westport and Galway,” said Villiers-Tuthill.

D’Arcy virtually imported trades people into the area because, “he saw the advantages it would bring to the area and to his own estate” said Villiers-Tuthill.

“(The people) came here because the advantages were here and the possibility of making a better life for themselves was here,” she said.

D’Arcy saw potential in the area and wanted to develop a fish station in Clifden, but according to Villiers-Tuthill the initial success was met with failure.

“Clifden was too far inland,” said Villiers-Tuthill. The fishing station was not successful.

“(Clifden) became a market town rather than a fishing station.” Clifden provided a market for the locals to sell their agricultural produce such as oats, potatoes, vegetables and fish.

“They were able to bring their goods into the market and sell them there. So it created a center,” Villiers-Tuthill said.

Rocky terrain aside, there are pockets of fertile land. Locals used seaweed to fertilize the land. “They still use it today,” Villiers-Tuthill said. If people live close to the shore and if they can bring seaweed in easily they will still use it according to Villiers-Tuthill.

Apart from fertilizing land, other uses for the local seaweed include, medicinal and cosmetic purposes. Seaweed baths in spas throughout the country are popular. According to Villiers-Tuthill a seaweed bath is “gorgeous!”

Numerous artists, authors and poets are drawn to Clifden specifically. Artists are attracted to Clifden by the light according to Villiers-Tuthill.

“I am told that the light is absolutely perfect for them and that they love it because of that,” she said.

J.R.R. Tolkien, author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings Trilogy, allegedly used the landscape of Connemara as inspiration for his fantasy landscapes.

“Writers came because of the solitude, and the fact that you experience a completely different world than even on the east coast of Ireland,” Villiers-Tuthill said.

“You have the feeling as you are driving through the rugged landscape of Connemara that you are breaking into another era, almost like another country,” she added.

Villiers-Tuthill is part of an eight member committee which has planned the upcoming bicentennial celebration of Clifden since 2009.

“We want to try to mark the occasion, interpret our history in as many ways as possible so as to make it acceptable to small children and to people who don’t have the slightest bit of interest in history,” to “those who are genuinely, deeply interested in history,” she said.

At present the plans involve the third annual Genealogical and Local History seminar on April 16. Speakers include Rob Goodbody, Paul Gosling, Siobhan Mc Guinness, Gregory O’Connor and Kathleen Villiers-Tuthill herself.

“The big one next year is the one we’re hoping people will come from abroad,”

Villiers-Tuthill said.

The planning of the big bicentennial celebrations is cheering up the locals amidst the recession and austerity measures according to Villiers-Tuthill. “It is raising the morale,” she said.

Locals are planning to bring the Irish Diaspora of Clifden and Connemara back for a 2012 celebration that promises Irish Music, traditional boat Regatta, and a number of seminars throughout the year. The main week of celebrations will be May 25 to June 4, 2012.

“We’re celebrating (the bicentennial) for ourselves and hoping that by putting on a genuine festival where the local people are involved and the local people are enjoying themselves that any tourists who come will actually be part of a local festival,” she said.

“We would love to have people come back and join in it, they’ll definitely find us in our best of form,” Villiers-Tuthill said.

For more information on the celebrations and the history of Clifden and the D’Arcy family visit www.clifden2012.org

Written by Loretto Horrigan Leary

Clifden 2012 Facebook Stream