Kathleen Villiers-Tuthill

Kathleen Villiers-Tuthill is a native of Clifden and the author of five books, two booklets and numerous articles on the history of West County Galway. Her work is based principally on primary sources, from public archives and private collections. In recognition of her contribution to the heritage of the county, she has received two Heritage Awards from Galway County Council. The first in 2003 and in 2006 her most recent book, Alexander Nimmo & The Western District, was granted Best Heritage Publication Award. Married with two sons, she divides her time between Dublin and Clifden. For more information on publications by this author click the site link below.

Website URL: http://connemaragirlpublications.com E-mail: This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

Senior citizens of Gortrummagh and Fakeeragh in 1836

On a recent trawl through early nineteenth century newspapers in the National Library, I found this fascinating item on the inhabitants of the townland of Gortrummagh and Fakeeragh in 1836. This rather interesting letter to the editor of the Galway Patriot, signed only with the initials J.H., was written on 19th May 1836, simply to draw attention to the great age attained by many of the author’s neighbours. The letter lists the names and ages of several people in the townlands and in many cases gives their relationship to each other.

To anyone with ancestors of the same name coming from this district, the information given here is invaluable. It is doubtful that any other record for this group of people exists. The majority of the people listed would have been the occupiers of smallholdings living on the D’Arcy estate, and no record of tenant leases for smallholdings from this early period seem to have survived for this estate. Almost certainly they were all Roman Catholic, but the church records for this parish only start in 1838 and were not complete in the early years, so there is little hope of finding them listed there. There is no point in checking the local graveyard either, as it was not customary to inscribe names on headstones at the time; the graves were simply marked by placing a stone at the head and foot of the grave.

And so we find that a simple letter to a newspaper editor, written by a man with a curiosity for people’s ages, an interest in mathematics and an obvious love for his locality, can perhaps, 175 years later, take some amateur genealogist back yet another generation in their family tree.

The letter begins:

“Perhaps the following curious circumstances may be found worth a place in your very valuable Journal. This day, at the funeral of a good old neighbour, an extraordinary instance of longevity arrested my attention. In the village of Gurtdroma, (that in which I drew my first breath, and the residence for more than two centuries past of my maternal ancestors,) there are now living in good health, eight persons, whose united ages make 697 years; their names are – John Prendergast, father of Mrs Lynch, of Salt-hill, Galway, 90 years; his wife Mary, 84; Patt Gaven, 85; Patt Cloonan, 85; Patt Keady, 81; Bridget McGrath, 99; Margaret Molloy, 87; Sibby Clisham, 86; and if to these we add the ages of Francis Lynch, Esq., of Omey, and Mrs Elizabeth Lynch (who till very lately lived within one mile of this place, and are now not far removed from it), the former 97 years and the latter 80, we shall then have 10 persons, whose joint ages make 874 years. I pray here to be permitted to observe that Francis Lynch never drank strong liquors.

It is a fact, not less striking, that there have lived on that limited tract, until within a recent period laid up with their fathers, fifteen persons, whose ages put together would make 1406 years, viz.: - My great grandfather, Edward Joyce, 110 years; he never tasted ardent spirits, never complained of ill health, and never had his sight impaired to his death; his son, Martin, 81; Martin’s mother-in-law, Mary King, 88; his sister Ellen, 63; her husband, Ulick Joyce, 98 – five persons in one family whose ages number 460 years; Michael Flaherty, 97; Margaret, his wife, 92; her mother, Kate, 105; Judy Keady, 102 (mother-in-law of the above named John Prendergast); James D’Arcy (husband of the above named Margaret Molley) 101; Matthias Clisham (husband of the above Sibby) 93; James Madden, 88; John Delap, 84; his wife, Margaret Pole, 89; and Patt Burke, father of James Burke, Esq., attorney, (who, a little before his death, which happened in December last, removed to Omey,) 95. In collecting the above information, I have this day had the statements of five of these persons, besides other most authentic testimony.

The purity, salubrity, and healthfulness of the air of this place have long been celebrated – to which, as well as the contiguity of the sea-bathing, many persons have attributed this unusual longevity. It may not be out of place here to observe that there are several springs of spa and mineral waters, (one of which John Prendergast and his family still drink of) to be found on this little region of long life.

This sweet interesting little village is situated within half a mile of Clifden castle, the delightful seat of Mr. D’Arcy, and not quite two miles from the town of Clifden. It is situated on a rising ground, and overhangs Ardbear Bay, one of the most beautiful formed by the Atlantic. The prospect from the hill above it extends on the South East to Arran and the co. Clare, 60 or 70 miles distant; on the South to the Brandon Hills, in Kerry, 90 miles; to the south-west and westward, as far as the boundless horizon permits the eye to reach. This view is, in fair weather, diversified with the sight of the various sized shipping, and, in rough weather, by a most tremendous breach of sea over the shoals of Slinehead. To the north-west, the view extends as far as Achill Head, and all the intermediate islands, 70 miles; to the northward, as far as the Reek, or Crough Patrick, near Westport, 40 miles; on the east, the hills of Joyce Country and Bunnobola interrupt the view, but ample compensate for this defect by their stupendous height and magnificent romantic appearance, about 20 miles distant. Taking it altogether, perhaps the united kingdom does not furnish so extended a prospect. I have been led into this digression to show, that besides being healthful the situation is exceeding pleasant.

I remain, Dear Sir,

Ever yours, faithfully,

J.H.

What a shame that the letter writer did not give his full name.

Kathleen Villiers-Tuthill

The Galway to Clifden railway was in operation for forty years from 1895 to 1935, it was a single line of standard gauge, 5 feet 3 inches, with a total length of 48 miles 550 feet. The line ran through central Connemara and had seven stations, Moycullen, Ross, Oughterard, Maam Cross, Recess, Ballynahinch and Clifden. It took five years to construct and cost over £9,000 per mile.

Work started on the line in the winter of 1890, during a time of severe hardship in Connemara. A period of distress prevailed throughout the region due to bad weather, crop failure and falling agriculture prices. The people were in need of urgent assistance and the government considered the construction of a railway line was the ideal way of offered large-scale employment over a wide area. Up until this, railways were built by private enterprise and several attempts to construct a railway linking Galway with Clifden had failed due to lack of funds. However, by 1888, the government had decided that, in order to advance the rail network throughout the country it would offer grants for the construction of railways in remote, thinly populated districts that were considered commercially non-viable by the railway companies.

The Galway to Clifden line was constructed by the Midland Great Western Railway Company at a cost of £410,000, with an additional £40,000 going towards rolling stock. A large portion of the cost, £264,000, was granted as a free gift by government, under the Light Railway Act (1889). The company was to build, maintain and operate the line.

There were two engineers and three contractors involved in the construction of the line. The engineers, John Henry Ryan and Professor Edward Townsend, were both graduates of Trinity College Dublin and Townsend was Professor of Civil Engineering at Queen’s College Galway. The contractors were Robert Worthington, Charles Braddock and Travers H. Falkiner.

In order to bring employment quickly to the people, a provisional contract was entered into with Robert Worthington and preparatory works were started in autumn 1890. By January 1891 there were 500 men working along the line, at an average wage of twelve shillings a week. Over 200 of these took up lodgings in Clifden to avail of the work, while others were accommodated in wooden huts along the route. Each hut contained ten beds and a stove, and in some huts there were two men to a bed.

As the work progressed, the engineers became unhappy with the standard of Worthington’s work and he failed in his bid to win the final contract. The contract instead went to Charles Braddock. In April 1891, Braddock had notices in place along the line offering employment to all who would apply; by May he was employing almost a thousand men and boys. However, a year later, Braddock was running up serious debts throughout the county and failing to pay his workforce. There was a strike along the line that was only resolved with the promise of more regular wages. This, however, proved false and when Braddock was eventually declared bankrupt the MGWR Company was forced to take back the works in July 1892.

The contract was then passed to Travers H. Falkiner, who went on to complete the major part of the work. Under Falkiner, at the height of construction, over one thousand men were given regular employment along the line and the number rose to one thousand five hundred on occasion. Skilled men were brought in from the outside but the local workforce carried out the majority of the labouring work. Supply huts were erected in Ballinafad to serve the need of the workforce and shebeen houses were opened along the line. Falkiner, with the support of the local priest, tried to have the shebeens closed down, but failed.

By far the most interesting feature on the line was the viaduct across the Corrib River, the stacks of which can still be seen today. This was made up of three spans, each of 150 feet, with a lifting span of 21 feet, to allow for navigation of the river. There was just one tunnel on the line; this was a ‘cut and cover’ that carried Prospect Hill roadway over the railway. In all there were twenty-eight bridges, thirteen small accommodation bridges (bridges under 12 feet span) and numerous culverts to facilitate the sudden increase of water following heavy rainfall.

The seven stations all had passing places or loops, with up and down platforms, except at Ross and Clifden. Those stations situated close to Galway were faced with limestone taken from local quarries, while others further west were of red brick and roofed with red tiles. There were 18 gatekeeper cottages, situated at level crossings on public road.

The line from Galway to Oughterard was opened on 1 January 1895 and the rest of the line came into operation in July. As had been hoped, the opening of the line assisted the development of agriculture and fisheries in the region and contributed greatly to the economic stability of the area, particularly through its role in helping to establish Connemara as a tourist destination. The route was never profitable and in a bid to improve traffic on the line, the company embarked on a determined marketing campaign, advertising widely and offering packages that included tickets from many destinations in England with accommodation at their hotels at Recess and Clifden. For the home market, during the years 1903 to 1906, there were special tourist trains laid on during the summer months, offering day trips from the east coast to the west.

The world war and local wars brought a decline in tourism in the early decades of the 20th century. In 1924 a merger of railway companies brought the Galway to Clifden Railway into the hands of the Great Southern Railway Company and the line was reported to be in need of a good deal of repair. Traffic had dropped due to competition from private haulage companies and an increase in private car ownership. Despite local protests, the Great Southern Railway Company took the decision to close the line and the last train left Clifden on 27 April 1935.

John D'Arcy (1785 - 1839)John D'Arcy founded Clifden in 1812. At the time, he was just twenty-six years of age, married and the father of three sons. He was also the proprietor of an estate that covered over 17,000 acres on the west coast of Connemara. The lands had been in the D'Arcy family for over 150 years, but they would be lost within a generation.

The D'Arcys were a Galway family, one of the fourteen powerful families known as The Tribes of Galway. The family seat was at Kiltullagh, near Athenry, but John was very much a Connemara man; his mother was a Lynch from Barna and his grandmother, also named Lynch, was from Drimcong in Moycullen.

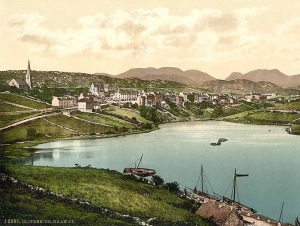

Ever since inheriting the family estates in 1804, it was John's ambition to establish a town on his Connemara lands. There were, however, many disadvantages to overcome and it would be years before the town would begin to take shape. Although slow to start, the town developed rapidly in the 1820s. The census figures for 1821 show the town as having 46 houses and a population of 290. By 1831, the population had jumped to 1,257 and there were 196 houses. Schools and churches dominated the skyline to the north of the town, while industrial buildings occupied the south; there was a brewery, distillery and mill on the banks of the Owenglin River River, next to the waterfall.

John D'Arcy died in 1839. At the time of his death, John's ambition had been achieved. Clifden was then the headquarters for the coastguard and police force for the district. It had a bridewell and before long there would be a courthouse and workhouse. The town was thriving and the economic benefits to the region were becoming clear as more land in the neighbourhood was brought under cultivation and agricultural production increased to supply the growing market.

Throughout the years of the Great Famine, Clifden became the centre for administering relief in Connemara. The town witnessed many painful scenes during this time, as the streets filled with starving people desperately seeking work, food or charity, and when these were exhausted, access to the workhouse. Many houses in the town became tenements to house those who had abandoned their holdings so as to become eligible for relief, creating a breeding ground for cholera that reached epidemic proportion in 1849. When one takes in to account the inmates of the workhouse and the jail, Clifden was the only townland in the parish to show a sizable increase in population in the 1851 census.

The Famine affected all classes and ultimately caused the ruin of the D'Arcy family. Hyacinth D'Arcy, John's son and heir, was forced to sell the town, along with the rest of the D'Arcy estates, in the 1850s. Thomas and Charles Eyre of Bath, England, eventually purchased the Clifden estate for £21,245. Representatives of the new landlords would live on at Clifden Castle until the close of the 19th century.

It took years to recover from the Great Famine and there was periodic crop failure and times of hardship in the years that followed. However, the opening of the Galway to Clifden railway line in 1895 did much to improve the economy of the town and helped to establish Connemara as a tourist destination. The opening of the Marconi Wireless station at Derrygimla in October 1907, and the arrival of the first transatlantic flight there on 15 June 1919, brought fame in the early years of the 20th century. The years immediately afterwards, however, saw war and destruction visited on the streets. On St Patrick's Day 1921, during the War of Independence, the Black and Tans burned fourteen houses and shot two civilians, one of them fatally, in retaliation for the shooting dead of two policemen by members of the IRA some hours earlier. In the Civil War there was a ten-hour battle fought in the streets between the opposing sides.

Recent years have, thankfully, been more peaceful. Since the foundation of the Irish Republic, the town has focused on developing a sound economy for the local population, relying heavily on the thousands of tourists who continue to visit each year.

With its beautiful landscape, plentiful activities and fascinating history it is no wonder that visitors fall in love with the capital of Connemara. In the past 200 years, the people of Clifden have displayed a resilience equal to that of the town's founder. Now in 2012 they can celebrate the rich and authentic heritage of their town with justified pride and confidence.